An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

Views of Fort Point: Fitz Henry Lane's Images of a Gloucester Landmark

(This essay originally was published in three parts in the newsletter of the Cape Ann Historical Assocation, now the Cape Ann Museum, in April, July, and September 2004.)

Fort Point in the 1840s

Fitz Henry Lane returned to live in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1848, having spent the previous sixteen years in Boston honing his art in lithography and oil painting.[1] The Harbor Village he had left in 1832 was then dominated by foreign trade, sending merchant ships to ports in Europe, the Caribbean, South America, and even as far as India. The ships were of the smaller classes of square riggers and schooners, and the merchants' wharves and counting houses occupied much of Harbor Cove's shallow confines. The remainder of Gloucester's Inner Harbor was largely devoid of commercial activity, save for scattered wharves and flake yards of individual fishermen and a few small fishing firms.

Harbor Cove was the logical choice for a merchant port. It had the deepest approaches (at high tide) to the town's waterfront, allowing ships to tie up to the wharves for unloading; however, it was so shallow at low tide that vessels larger than boats were grounded—a problem not remedied by dredging until the 20th century.[2] Most of the merchants' wharves lined the north side of the cove, parallel to Front Street (as the western end of Main Street was then called). Some wharves followed the shore of Duncan's Point, but stopped short of its rocky extremity.

The west side of Harbor Cove was dominated by the high ground of Fort Point on whose summit sprawled the crumbling remains of Fort Defiance. Originally built as Fort Anne during the Revolution, it became Federal property in the 1790s and was rebuilt and re-garrisoned during the War of 1812. Following that conflict, it was again abandoned and left in isolation until the Civil War, when it was rebuilt and reactivated for the last time.[3] At the time of Lane's return, it was the sole occupant Fort Point's promontory, save for a wooden building then used as a bowling alley.

Goucester in 1848 was a port on the verge of making major changes. Preoccupied with foreign trade, it left most of the fishing to be carried on in other Cape Ann harbors: Sandy Bay, Pigeon Cove,[4] Lanesville, and Annisquam. In fact, Massachusetts was no longer the leader in the New England fisheries, having ceded its primacy to Maine. In the 1850s, this was to change as Boston absorbed Gloucester's foreign shipping and new fishing methods spurred a modernization of the fishing fleet. Improvements to the waterfront kept pace and an expanding fishing industry took over every usable part of the Inner Harbor's shoreline. Rail connections and steamship service to Boston cemented Gloucester's economic ties to northern urban centers and guaranteed a market for all the fish it could catch.[5]

Figure 1. View of Gloucester, (From Rocky Neck), 1846 (inv. 57). Colored lithograph, 21 ½ x 35 ½ in.

Manchester Historical Museum, Mass.

Lane's 1846 lithograph View of Gloucester from Rocky Neck (Figure 1) was based on an oil painting he had done two years earlier. This image sets the stage for the artist's visual record of the harbor and its development to the early 1860s.

Between the rocky projections of Fort Point and Duncan's Point lies the snug and prosperous Harbor Cove. Beyond Duncan's Point, east to Vincent's Cove and Vincent's Point, the wharves and flake yards are early signs of a reviving fishing industry. Harbor traffic includes the side-wheel steamship Yacht — not a yacht in fact, but the first commercial steamer to carry passengers and freight between Boston and Gloucester.[6] The mix of vessels and harbor activity was probably meant to be typical of the period: a window on a more tranquil maritime community and its promising waterborne enterprises.

The view from Duncan's Point

Before his return, Lane had explored the harbor on numerous visits in the 1840s, making a particularly detailed visual record of the Fort as seen from Duncan's Point. With Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point in the background, the juxtaposition of these low land masses on a plane of water offered a tranquil, spacious setting that was eye-pleasing in its own right, yet receptive to illumination and atmospheric effects as well as arrangements of ships and human activity. It is tempting to speculate that this scene so pleased Lane that he built his stone house where he could enjoy the view daily. At least five of his finished paintings document it: two from 1847 or earlier; two from 1848; and one from 1850.

This was a period when Lane's painting style was making important changes in treatment of composition, in use of color, and in the development of brush techniques that marked his mature handling of light. No less important were changes to Fort Point with the addition of new wharves and buildings, and the ships and activity which these additions attracted. All were to be documented in detail in the succession of Lane's paintings.

Figure 2. The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 28). Oil on canvas, 12 x 21 1/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum.

What is very likely the earliest known depiction by Lane of Fort Point is an undated oil on canvas (Figure 2) which probably served as a color sketch for the finished painting in Figure 3. The colors of the landforms are chromatically accurate, but the sky and sea are flat gray tones, devoid of surface detail. Lane may well have painted it on a cloudy day, when colors are seen more accurately, to use for reference in his Boston studio when making a finished painting.

When comparing the color sketch with the painting, it is remarkable how faithfully Lane rendered the harbor geography, moving or distorting nothing in the process of transferring these forms from one canvas to the other. This fidelity to his sketches is readily apparent whenever these are available for comparison with their derivative paintings.

The color sketch also points out aspects of the sequence Lane followed when he painted the components of a harbor scene. Over ground colors for the sky and water, the land masses were applied in smooth opaque coats of basic colors for rocks, grass, buildings, seaweed, etc. These features were then shaded and detailed with thin transparent glazes and very fine line work.

At this point, the color sketch was complete, having all the eyewitness information the artist needed. In the case of a finished painting, this state was the starting point for a succession of opaque paint layers and transparent glazes which would give depth and surface detail to the water, produce cloud formations in the sky, and create atmospheric phenomena via refracted and reflected light. The results would be a realistic scene, suffused in an aura of tranquility and stilled motion, so characteristic of Lane's best work.[7]

With the harbor setting completed, ships and small craft were added to balance the composition and lead the eye to a desired area or point of interest. Painting these elements was much like painting the land forms, starting with opaque ground colors, over which shading and detail were applied in glazes and fine linework. Permutations of color to reflect the atmospheric effects in the background were essential to preserve the mood of the picture. The finished work often had such unity of composition, color, and mood that few suspect that such a painstaking additive process was used.

Figure 3. The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30). Oil on canvas, 22 x 36 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the Collection of Addison Gilbert Hospital, 1978 (DEP. 201.)

In the painting in question, The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Figure 3), we see this additive process brought to fruition. The setting is a very accurate transposition of the color sketch, the only compositional change being the lowering of the horizon and cropping of the rocks in the foreground. The painting is undated and the attributed date, 1850s, seems questionable. Both painting and sketch depict Fort Point as it looked in 1847 or earlier, and the sketch could date as early as 1842, given its similarity to another sketch of Harbor Cove bearing that date.[8] Stylistically, this painting has qualities which suggest that it is from an earlier period. The cloud formations are evocative of those in Lane's lithographs, and the range of colors is very restrained, relying more on values as a lithographer would.use them in a monochromatic image.

In a recent publication, a Lane painting of the same subject from a slightly different vantage point, dated 1847, shows that Lane had already gone far in experimenting with atmospheric effects and illumination of the scenery.[9] The painting in Figure 3, with its less sophisticated treatment of light and color, seems to be closer in date to Lane's harbor scenes of the mid-1840s. If the color sketch can be assigned (conservatively) a date of c.1844, the painting itself was probably finished between that date and 1846.

Lending support to this earlier date are the vessels depicted, all of them being of older hull types with details of rigging which can be traced back two decades or more. The two schooners in the center foreground are of particular interest. At left is a topsail schooner which differs little from its counterparts in ship portraits of the 1820s. At right is a pink-stem fishing schooner called a jigger, a transitional form of the Chebacco boat which evolved into the pinky early in the 19th century.

The Eve of Development, 1848

Lane finished a third view of Fort Point in its undisturbed state in 1848, further developing his skills in working with light and reflections.[10] This painting may have been derived from a drawing made the previous year, for 1848 saw the beginning of major changes to the land and shoreline on the east side of Fort Defiance. In that year, Gloucester's most rambunctious merchant and entrepreneur, George H. Rogers, began the development of that site.[11] The last of the town's merchants to carry on trade with Surinam, Rogers wanted a wharf in the deepest part of Harbor Cove to minimize the cost and time of lightering (unloading offshore) a deep-loaded ship before it could be brought in to his old wharf off Front Street. Fort Point offered a solution, and Rogers was able to acquire land for a house and harbor frontage for a large wharf and storage sheds.

Figure 4. The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58). Oil on canvas, 20 x 30 in.

Newark Museum, N.J., Gift of Mrs. Chant Owen, 1959 (59.87).

The timing of all this construction is not completely clear, but another 1848 painting titled The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Figure 4) shows the completed house set into the banking below the fort and two vessels on or near the adjacent shore. One is a hulk, its spars and rigging removed, in the process of being broken up for salvage. What is not worth saving will be hauled ashore and used as back fill for the stone bulkhead which will stabilize the land connecting to the finished wharf.

The other vessel is a stone sloop, a single-masted sailing vessel of very sturdy construction, fitted to carry stone and commonly used as a floating derrick in the building of stone wharves and bulkheads. In this view, the mainsail has been triced up, i.e., hoisted part way up the mast to provide space for the loading boom to pivot.

This painting depicts Fort Point from the foot of Duncan's Point, probably at the wharf of William Collins which is seen in the foreground. Of all of Lane's views of Gloucester, this is the only one which depicts a ship under construction. In the background, Ten Pound Island is partially obscured by Fort Point; Eastern Point and its lighthouse lie off in the distance at the left.

Beyond Collins' wharf is a variety of shipping, the merchant ship (far left) and the merchant brig (far right) being components of Gloucester's foreign trade. The brig is tied up to George H. Rogers' old wharf for unloading. Note its disconnected extension which this foxy merchant built to gain access to deeper water, no doubt exploiting a loophole in harbor regulations limiting the length of wharves. The topsail schooner (center left) is just arriving with a deckload of lumber, probably Maine spruce and pine for building houses. The two fishing schooners (center right) share a mooring; they have unloaded their fish and are awaiting outfits for their next trips to the fishing grounds.

Despite the considerable activity in this scene, Lane succeeded in stopping the action and captured a split second of tranquility, bathed in the warm sunlight of a late afternoon. He would not find many more such moments in this location as Gloucester entered a new decade and a new chapter in its maritime history.

Fort Point Transformed, 1850

In 1849, Fitz Henry Lane built his seven-gabled stone house on the rise of land overlooking Duncan's Point, sharing the building with his sister, Sarah Ann and his brother-in-law, Ignatius Winter.[12] For this reason, the house was identified as "Winter & Lane" on an 1851 map of Gloucester (Figure 5). This location gave him an already familiar view of Fort Point, although from a higher elevation than he preferred for his pictures of that scene. In 1850, he painted yet another picture of the Fort and Ten Pound Island, which differed markedly in visual content from its predecessors.

Figure 5. Detail from "View of Gloucester Harbor Village," in H.F. Walling and John Hanson, M~12 of the

Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex County, Massachusetts (Philadelphia: 1851). Cape Ann Museum.

While Lane's house was going up, on the opposite shore George H. Rogers was building his new wharf and store houses on the previously deserted east side of Fort Point.[13] The large dormered building adjacent to Fort Defiance hid most of the latter's remains from view, while the sprawling pier and its sheds gave the shore line a completely different character. Only Ten Pound Island in the background stayed the same amidst the onslaught of progress.

Vessel traffic in Gloucester Harbor had increased as well. New schooners were added to the fishing fleet[14] and vessels in the coasting trade made more visits than ever to meet a growing local demand for salt, lumber, firewood, hay and a multitude of foodstuffs and bulk goods. These "coasters," rigged as sloops, schooners, and brigs, still offered bulk shipping at lower costs than rail shipment.[15]

Figure 6. Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240). Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 in.

The Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, VA.

Looking out over this activity, Lane must have found these changes affecting, if not dismaying. His 1850 depiction of this scene (Figure 6) is much the busiest and may have been his last. No later versions have so far come to light and there are no notes on his drawing to indicate that he used this composition for subsequent paintings.

In addition to the progress it documents, the painting is notable for the qualities of light and the atmospheric effects, by which it conveys the tranquility of a late summer afternoon. A hazy yellow sun shines through broken clouds over the horizon at far right, while wisps of clouds aloft reflect touches of yellow sunlight against the reddening sky. These colors tint the reflections of rocks, buildings, and the nearly still water surface.

These aspects held promise for what might have been an important example of Luminist painting—perhaps Lane's most successful effort to depict this particular scene.[16] That promise was seriously compromised by the presence of so many vessels which break up the receding plane of the water surface and the sense of spatial depth it could have created. The tranquility is disturbed by the perceived motion of vessels under sail and by the human activity in the foreground. The composition itself is overwhelmed by too much detail.

For whom, and why, Lane painted this picture is as much a puzzle for maritime historians as it is for art historians. If it is not a prime example of Lane's artistic achievement, it is undeniably one of the finest visual documents of merchant shipping in a mid-19th century New England harbor. Did Lane paint it for Rogers, whose wharf is featured so prominently? If so, why is a bark, the only likely Surinam Trade ship present (Figure 8, Item 19), almost completely hidden from view? Or did Lane paint it on his own account, as a personal statement on Harbor Cove shipping in a time of great changes? For now, its provenance can only be traced back to 1946.

Figure 7. View in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 143). Graphite on paper, 9 1/2 x 34 ¾ in.

Cape Ann Museum.

As interesting as the painting is Lane's drawing (Figure 7), which outlines the scene in detail before all of the vessels were added. Here, we can examine Rogers's Wharf without obstructions and find that the pier was not yet completed at its south-east end (at left), where a tripod hoist can be seen setting timber pilings against the stone bulkhead. Two vessels are in this drawing: a coasting schooner (left panel) and a square-sterned New England boat (right panel). Lane included the schooner as a necessary reference for the proportioning of other vessels in perspective. The boat appears in two previous paintings and may have had some personal significance to the artist.

Of great importance is the set of perspective lines which converge at a vanishing point just to the left of Rogers' Wharf. From these diagonals, isometric lines are projected horizontally so they intersect the schooner at its waterline, rail, and main mast head. The spaces between these lines will define these proportions for vessels placed elsewhere on the same vertical plane. Similar isometric lines can be constructed from the diagonals to find the proportions of vessels of other dimensions, or of vessels at other distances.[17] This is the only one of Lane's known drawings which shows this exercise, implying strongly that he had planned from the outset to include a large number of watercraft, and that extra care would be needed to place them and to gauge their proportions.

Such planning and disciplined layout work presupposes a collection of vessel images on file for inclusion in the finished painting. Given Lane's experience in ship portraiture and his practice of painting vessels over the backgrounds, it seems certain that he kept a folio of his drawings of ships and boats, together with sketches and notes on aspects of hull form, rigging, and fine details. Only a few of these drawings have survived.

For much of his nautical source material, Lane drew from life, but his knowledge of naval architecture implies that he had access to textbooks on the subject and was allowed in shipyards and sail lofts to study hull designs and sail plans.[18] As the son of a sailmaker,[19] he must have known some of his father's fellow artisans and had access to their sailmaking drawings, as a recent discovery in the archives of the Cape Ann Historical Association seems to bear out.

| 1. Remains of Fort Defiance. | 10. Stone anchor, or "killick," for mooring the shellfish car. |

| 2. Wharf and buildings of George H. Rogers | 11. Yawl boat. |

| 2a. Ignatius Winter's windmill, removed from the site of the Pavilion Hotel in 1849. |

12. Merchant topsail schooner. |

| 3. Wharf and buildings of John W. Lowe | 13. Lumber schooner. |

| 4. Ten Pound Island. | 14. Lumber schooner with square topsail rig. |

| 5. New England boat, square-sterned type. | 15. Sloop. |

| 6. New England boat, double-ended type. | 16. Hermaphrodite brig, or "half brig." |

| 7. Gill nets and fishing gear being off-loaded from the double-ended New England boat. |

17. Fishing schooners. |

| 8. Gutting and washing fish. | 18. Fishing schooner, see Figure 9 |

| 9. Shellfish car, for keeping clams, crabs, and lobsters alive for market. | 19. Merchant bark, type used in the Surinam Trade. |

Figure 8. Key to vessels, landmarks, and human activity in Figure 6.

A book of sail plans, compiled by William F. Davis and dated 1845,[20] contains numerous plans for fishing schooners, all of them drawn in a very simplified way. The single exception is a conventional plan over which a hull has been beautifully rendered in pencil (Figure 9). The drafting is freehand, but the graceful curves of the rail and sheer are so smooth that they seem to have been drawn with ship curves. The hull is shaded to show realistically its shape, particularly at the bow and stern. The beakhead is fitted with trailboards and a billet (scroll) head which show a delicate tracery of carvings. The hull is depicted as floating in water whose ripple patterns closely resemble those in the painting.The fine drawing technique alone points to Lane as the likely draftsman, particularly when the date of the sail plan book is considered. The argument is further strengthened when this drawing is compared with a fishing schooner in the painting (See Figure 8, Item 18). For the latter image, Lane added three more sails, but the similarity of the hull to that in the drawing seems more than coincidental.

If we can accept the embellishments to the Davis sail plan as Lane's work, we have a rare surviving example of the artist's use of a vessel's design drawing for a subject in his painting. Coupling this find with Lane's drawing of the harbor setting, we can better appreciate his methods of composition through a lengthy and exacting process of drawing a scene, the individual ships and boats, and combining the two when the painting is well along.

But we should also appreciate Lane's control over the process. His approach to a composition may at times have been more calculated and less intuitive. His depiction of Gloucester's Harbor Cove in 1850 may have sacrificed some of those qualities we attribute to Luminism, to the disappointment of art historians, but historians of Gloucester's shipping and maritime commerce could hardly ask for a more revealing and informative visual record of that activity at that period.

Figure 9. Sail Plan of an Unidentified Fishing Schooner, c.1846 (not published) in a sail plan book titled William F. Davis, Gloucester.

Graphite on paper, page size 20 x 14 in, image size 9 1/2 x 14 1/2 in., scale 1/8" = 1'. Cape Ann Museum.

Fort Point in the 1850s

When George H. Rogers' wharf was depicted by Lane in his 1850 painting (Figure 6) and in maps of the early 1850s (Figures 5 and 10), only the solid core of stone bulkheads and backfill had been completed. Over this grew a large complex of sheds and storehouses, and in due course the wharf was extended over wood pilings into deeper water. A chart of Gloucester Harbor (Figure 10) shows only too clearly the incentive for merchants to extend their wharves beyond the shallows and rocky flats that lined Gloucester's Inner Harbor. The expansion of Rogers' wharf gave it the deepest frontage of any wharf in Harbor Cove and a great advantage over his competitors.

George H. Rogers was more than just a mover and shaker in Gloucester's foreign trade. He quite literally moved buildings, in whole or in pieces, using the Gloucester landscape as a chessboard, whereon he rearranged the business district, residential neighborhoods, and built up undeveloped areas. His own house at 21 Middle Street was built around the interiors of two fine Boston houses which he had salvaged; he also transplanted a Boston bank building, stone by stone, and rebuilt it on Front Street, now 109 Main Street.[21] In transplanting these buildings, barge transportation was necessary, and Rogers' sturdy new wharf provided the ideal offloading facility.

Figure 10. Detail from U.S. Coast Survey chart, Gloucester Harbor, Massachusetts (Washington: electrotype copy issued October, 1887).

Depths in shaded areas are in feet; in unshaded areas, in fathoms. Private collection.

Ignatius Webber’s Wandering Windmill

Among the buildings Rogers transplanted the windmill built by Ignatius Webber in 1814 was certainly the most picturesque. First depicted in the famous 1817 engraving of Gloucester Harbor and the Sea Serpent,[22] it was still in use in 1836 when Lane included it in his first lithograph of Gloucester Harbor. By the time Lane made his second lithograph in 1846 (Figure 1), the windmill was still visible, minus its vanes, just behind the ruins of Fort Defiance.

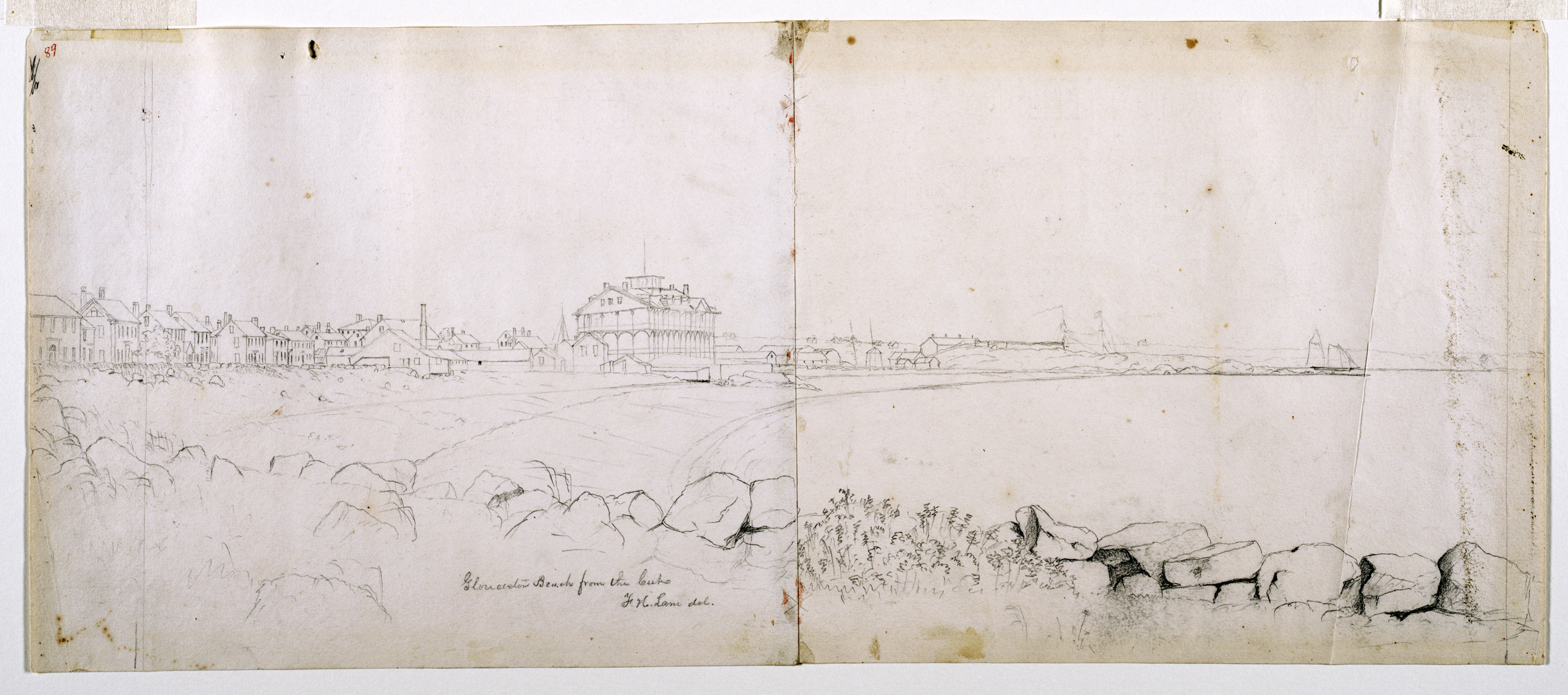

When Sidney Mason built the Pavilion Hotel in 1849, the windmill was acquired by Rogers and moved to the foot of his new wharf, close by Beach Street (figure 5). This relocation was recorded by Lane in his 1850 painting of Fort Point and its sketch (Figure 8, Item 2A). Lane also showed it in this new location from another viewpoint, in one of his three surviving sketches of the Pavilion Hotel (Figure 11). Winter's windmill was to remain on Rogers' wharf until its destruction by fire in 1877.[23]

Lane's drawing is also of interest as it shows the undeveloped west side of Fort Point and how Fort Defiance dominated the approach to Gloucester's Inner Harbor, hence its strategic value in defending the town in wartime. It also illustrates the low-lying neck of sand and gravel which connected Fort Point to the rest of the town. This stretch was mostly occupied by flake yards for drying salt cod and remained so-used throughout the 19th century.

Figure 11. Gloucester Beach from the Cut, 1850s (inv. 103). Pencil on paper, 8 3/4 x 21 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum.

Figure 12. View of Gloucester, Mass., 1859 (not published). Two-tone lithograph, 24 3/4 x 33 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum.

Zenith of the Surinam Trade

At the time of Lane's 1850 painting of Fort Point, Gloucester's foreign trade was focused on Surinam, or Dutch Guiana, and amounted to $102,439 in exports and $71,043 in imports.[24] By 1857, two years after Lane's third and last lithograph of Gloucester Harbor (Figure 12), the trade had reached its high point with exports of $374,461 and imports of $377,061.[25] When Lane's lithograph is studied closely, the reason for this dramatic growth is not hard to find. With his greatly expanded wharf facilities, George H. Rogers had outstripped his rivals and become the dominant figure in the Surinam trade. The variety of buildings on his wharf bespoke the wide variety of goods his ships carried and the need to handle and store them in specific ways.

But Gloucester had grown as much in the foreign trade as its harbor's limitations would permit. A shallow harbor prevented the berthing of larger ships and the variety of export goods then in demand strained the Gloucester merchants' abilities to provide them. Boston Harbor was deep enough to handle any size ship at wharfside and Boston merchants had fewer logistical problems in providing export goods.[26] Even as Gloucester peaked, her Boston rivals were making inroads in this trade, prompting Rogers to consider its future and his role in it. In 1860, he moved his office and ships to Boston, and Gloucester's Surinam trade shrank to one or two voyages a year for most of the 1860s.[27]

Fort Point after Lane

Lane's 1855 lithograph offered the last dated view of Gloucester Harbor in which he depicted Fort Point in any detail. The ground around Fort Defiance was being covered with houses while the remaining shoreline was soon to be built out for additional wharfage, leaving not a hint of the point's appearance when Lane first sketched it. So extensive was the build-up that even Ten Pound Island was partially obscured from view.

This period saw Lane turn his attention from Gloucester's Inner Harbor to the Outer Harbor, its entrance, and its western shore. It was also a time of extensive travel along the Maine coast and exploration of Penobscot Bay, where he found inspiration for many of his greatest luminist works.[28]

When Lane's pictorial record of Gloucester ended, photography had become available to resume the task. Stereograph images of Gloucester began to appear in the 1860s and remained popular to the end of the century, but were limited in their ability to capture detail. Large format photography did not become common until the 1870s, but when it did, the results were impressive, as William A. Elwell's view of Harbor Cove (Figure 13) clearly shows. Ignatius Webber's windmill is shown with an arrow.

Figure 13. William A. Elwell, View from Belmont House, of a Fishing Wharf, with the Old Fort of 1812.

Albumen print from a published album titled Gloucester, 1876. From a copy negative in a private collection.

Figure 14. Detail from a stereograph of Harbor Cove taken in 1871 (photographer unidentified).

The unfinished clock tower of the newly rebuilt City Hall is still covered with tarpaulins. Cape Ann Museum.

The exodus of Gloucester's Surinam trade only made more room for her rapidly expanding fishing industry, and the re-building of Harbor Cove to accommodate larger wharves and fish handling facilities proceeded apace. A few of the Surinam merchants' buildings survived on Fort Point, including most of Rogers' buildings, the old windmill, and the gambrel-roof buildings on John W. Lowe's wharf (Figure 13). Most of them were destroyed by the fire of 1877, making way for even more intensive development of the area.

Lowe's wharf buildings were even older than Ignatius Webber's windmill, probably dating to the late 1700s, if not earlier. Their unique looks provided reference points and a thread of continuity in Lane's series of Fort Point views. A stereograph (Figure 14) offers the only close view of one of them, situated below the weedcovered remains of Fort Defiance. Surrounded by urban growth and waterfront renewal, this relic awaited its fate as the port of Gloucester set its past aside, forgot its greatest artist and moved on to become one of the world's great fishing ports.

[1] John Wilmerding, Fitz Hugh Lane (New York: 1971), pp. 19, 36.

[2] This problem is evident when examining early hydrographic charts of Gloucester Harbor. According to 1853 soundings by the U.S. Coast Survey, the depth of Harbor Cove varied from one to six feet at low tide.

[3] Joseph E. Garland, The Gloucester Guide (second edition, Rockport: 1990), p. 138.

[4] John J. Babson, History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann (reprinted, Gloucester: 1972), pp. 543, 544.

[5] Wayne O’Leary, Maine Sea Fisheries (Boston: 1996). This book describes in rich detail the rise of Maine's fishery industries and its doomed rivalry with Gloucester.

[6] Charles Rodney Pittee, "The Gloucester Steamboats," in The American Neptune, Vol. XII (1952), pp. 288, 293, and Plate 26. The author incorrectly gives 1847 as the year this vessel was put in service.

[7] One unfortunate way to appreciate Lane's brush technique is to examine his paintings which have been cleaned too vigorously, a process that strips away some of the surface glazes and fine line work. When ships under sail are mistreated in this way, the sails become transparent, allowing the over painted background to be seen.

[8] See Plate XXVII, Image 109 in The American Neptune Pictorial Supplement VIII (Salem: 1965). The date in the caption is incorrect and the present whereabouts of the painting is unknown.

[9] Kristian Davies, Artists of Cape Ann, (Rockport: 2001), pp. 8, 10,11.

[10] See Gloucester Harbor, 1848, cat. 6 in John Wilmerding (ed.), Fitz Hugh Lane (exhibition catalogue, Washington and Boston: 1988; published in Washington and New York: 1988).

[11] For a colorful description of this colorful character, see Chapter 6 in Alfred Mansfield Brooks (Joseph E. Garland, ed.), Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester: 1974).

[12] Wilmerding, Fitz Hugh Lane, pp. 39, 40.

[13] Brooks, Gloucester Recollected, p. 62.

[14] Babson, History of the Town of Gloucester, pp. 573, 574.

[15] John F. Leavitt, Wake of the Coasters (Middletown, CT: 1970). A first-hand description of the early 20th century New England coastal trade, which had hardly changed since Lane's time.

[16] See Barbara Novak's essay, "On Defining Luminism," in John Wilmerding (ed.), American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850-1875 (Washington, DC: 1980), pp. 23-29.

[17] Elliot Bostwick Davis, Training the Eye and the Hand: Fitz Hugh Lane and Nineteenth Century American Drawing Books (Gloucester: 1993), pp. 24, 25.

[18] Erik A. R. Ronnberg, Jr., "Imagery and Types of Vessels," in Wilmerding, American Light pp. 67, 68.

[19] Wilmerding, Fitz Hugh Lane, p. 17.

[20] Hand-titled William F. Davis, Gloucester, 1845, the clothbound cover contains two unsewn, unpaginated signatures. Most of the plans are undated.

[21] Brooks, Gloucester Recollected, pp. 62, 63.

[22] James R. Pringle, History of the Town and City of Gloucester, Cape Ann, Massachusetts (Gloucester: 1892), pp. 104,105, and half-tone plate.

[23] Mary Ray (comp.) and Sarah V. Dunlap (ed.), Gloucester, Massachusetts Historical TimeLine, 1000-1999 (Gloucester: 2002), pp. 152, 153

[24] Commerce and Navigation, Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, ending Tune 30, 1850 (Washington: 1851), pp. 42,264.

[25] Commerce and Navigation, Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, ending Tune 30, 1857 (Washington: 1857), pp. 510.

[26] Samuel Eliot Morison, The Maritime History of Massachusetts (Boston: 1921), pp. 215, 225, 229.

[27] Commercial Relations of the United States with Foreign Nations [Report of the Secretary of State for the year ending September 30, 1861] (Washington: 1862), pp. 200, 201.

[28] Wilmerding, Fitz Hugh Lane, pp. 75, 76, 80-83.