loading

Fitz Henry Lane

HISTORICAL ARCHIVE • CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ • EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE

An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

Catalog entry

inv. 563

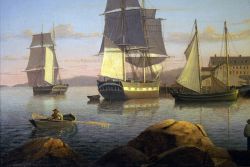

Gloucester Harbor at Dusk

Gloucester Harbor

c. 1852 Oil on canvas 24 x 36 in. (61 x 91.4 cm)

|

Commentary

From the boulder-strewn south west corner of Duncan’s Point and looking west south west toward Fort Point, this view captures the completion of George H. Rogers’ wharf on Fort Point’s east side, which dates the painting to 1852 at the earliest. This painting completes the progression of shore side harbor development chronicled in Lane’s remarkable series of at least eight Inner Harbor paintings dating from 1847-52 (see Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23), The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58), View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97), The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271), Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240)).

More wharves and buildings were to appear along the south east shore in the following decade; this suggests that the picture was painted soon after the completion of the east side facilities, and it further suggests that Rogers, or one of his associates, was involved in its commission.

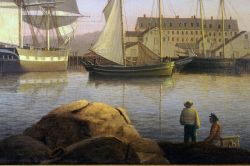

Beyond Fort Point lies Gloucester Harbor’s western shoreline with Norman’s Woe Cove and Norman’s Woe Rock at the painting’s left margin. In the right background the wooded hills of West Gloucester rise above Fort Point’s sandy causeway with its flake yards and wharves. Beyond, at far right, rises Sidney Mason’s Pavilion Hotel, built in 1849 to serve a growing tourist trade. This work shares the same crystalline light of the other works in the series; here Lane depicts a moment just before sunset with the sun casting strong shadows in the foreground and highlighting the half brig’s mizzen sail and gun ports leading the eye to Rogers’ large new building in the distance.

Afloat is a variety of watercraft reflecting aspects of Gloucester’s transition from a harbor of mixed trades to a port focused on a growing fishing industry. Most prominent is a brig (1), most likely used in the Surinam Trade, in which Rogers was heavily involved. Ever larger vessels used in this trade probably spurred Rogers to build his new wharf in deeper water at the entrance to Harbor Cove, but this move couldn’t keep up with the trend in vessel size. Along with other Gloucester merchants, Rogers moved his ships, warehouses, and office to Boston, leaving his new wharf to serve a growing fishing fleet.

At left is a hermaphrodite brig (2), or “half brig” in New England nautical parlance, a type commonly used for longer passages in the coastal trade and with West Indian ports. The stern galleries (a row of windows across the transom) indicate a vessel of higher class, fitted for carrying passengers and cargos of higher value.

To the right of the brig is a “jigger”(3), a Chebacco boat converted to a schooner rig by adding a bowsprit and setting a jib. This example is of particular interest, her square stern indicating that she was a Chebacco boat variant called a “dog body” prior to her rig conversion. In The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), Lane has shown a similar conversion of a pink-stern Chebacco boat. By the 1850s, this type was no longer built, but those which survived were of durable construction and still active in coastal fisheries and fishing banks in the Gulf of Maine.

Just beyond the jigger, tied up at Rogers’ wharf, is a banks hand-lining schooner (4), its bluff bow and stern davits for shipping a yawl boat proclaiming a life of hard work and few comforts for its crew. Near the right margin is a newcomer to the fishing fleet—a sharpshooter fishing schooner also fitted for hand-lining, but with a more finely-modeled hull to increase speed. The 1840s and ‘50s saw the development of fast-sailing schooners capable of returning to port with the catch on ice for shipment and sale of fresh fish to distant inland markets. Thanks to the railroads, a wider market welcomed Gloucester’s fish while Gloucester’s growing tourist industry welcomed summer visitors.

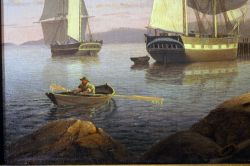

Lane was no less observant of humbler small craft, as seen in the painting’s foreground. Approaching from the right—under sail instead of being rowed—is a yawl boat (5), seemingly headed for a sailor who is seated on his sea chest. Is this a Gloucester version of a water taxi? At sea, yawl boats served as a fishing schooner’s lifeboat or for visiting other vessels; in port it was used to convey the captain to and from shore for official business, or to bring crew to and from the schooner for visits ashore or departure. Yawl boats retired from fishing filled useful roles in the shore fisheries, transportation about the harbor, or as “party boats” for sightseeing and sport fishing.

At left, a man in a dory (6) is rowing toward Rogers’ wharf, his mission indiscernible. In this period, dories were used in the shore fisheries; “dory trawling” using long lines with multiple hooks was then in its infancy and so far no record of its use has been found in Lane’s work.

–Erik Ronnberg