An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

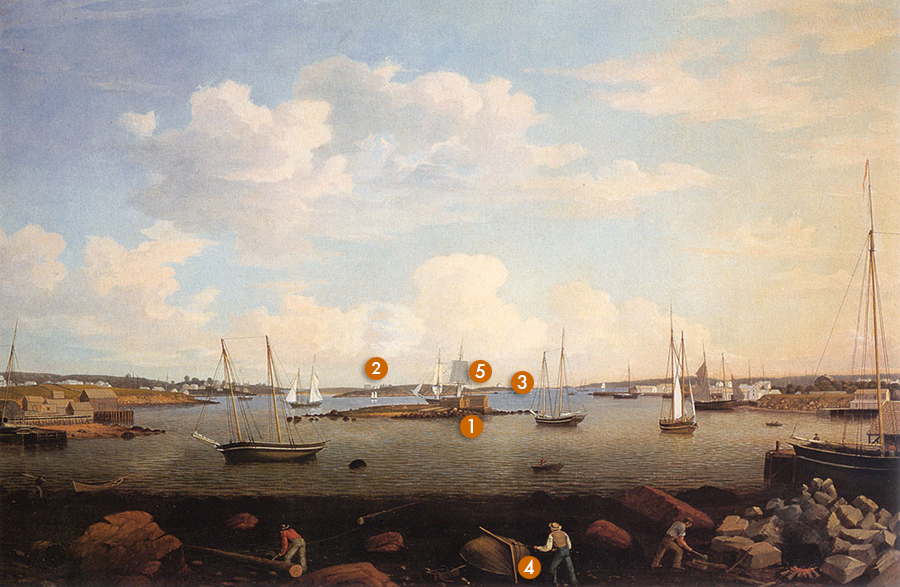

This is one of the great early Inner Harbor scenes in which Lane tries to capture his whole world in one view. The expansive panorama encompasses the whole of Gloucester's Inner Harbor: the wharves on both sides, Five Pound Island with its small fish shacks in the center of the view, and, in the distance, Ten Pound Island with its lighthouse. The dark arc of the foreground beach acts as the proscenium for a theatrical stage on which all the vessels and buildings enact their individual roles in the daily drama of a working harbor.

The view is taken from the shore at the head of the harbor—its innermost recess (see map below). On the beach in the foreground the center figure is tarring the seams of the boat he has just caulked using the material and tools from the box to his left. The man on the right chops wood for the black kettle that is now heating the tar to make it spread more easily. The man on the left is levering a large timber to follow the one already headed towards the water. These are pilings to be driven into the mud to hold the large rocks piled on the beach. The men are making a new cob wharf like the one shown in the extreme left-middle ground. The two wharves on the left side of the painting are the best depictions of crib and cob wharves to be found in Lane's Gloucester Harbor scenes.

The vessels in the harbor (mostly schooners with a brig directly behind Five Pound Island) are in various stages of anchoring or making themselves fast for the night. The tide is at dead low, and Lane is illustrating the problem with the Inner Harbor of the 1840s: there is not enough deep water at low tide to accommodate larger vessels. Note the vessel tied to the wharf on the far right. It sits entirely on the beach, although it will float on a high tide. The schooner on the left is leaning on its side in the shallow water and will need a few more feet of tide in order to float.

Lane is showing the beginnings of a new era of wharf building that would accelerate over the next two decades until almost the entire harbor was ringed with wharves. They extended far enough into the harbor to take vessels in all tides, greatly increasing the capacity and efficiency of the harbor. Fish could then be unloaded directly onto the wharves and flakes (fish-drying racks) shown beside the buildings on the left and on Five Pound Island in the center.

Lane did a number of similar paintings of harbor views between 1847 and 1850: The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271), View of Gloucester Harbor, 1848 (inv. 97), Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), and The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58). They all have a panoramic scale; one can almost see the curve of the earth in their scope. They are full of a fascinating array of activities—the everyday business of a working harbor. They have a fresh, crystalline quality of light that communicates the optimism of a town creating a new identity after the many decades of economic hardship brought on by the War of 1812.

– Sam Holdsworth

A Visual Guide to the Painting

Lane’s move from Boston back to Gloucester (late 1840s) marked a flurry of canvases depicting the town and its harbor from many viewing points. While the scenes of Harbor Cove are the most numerous and best known, other locations along the harbor shoreline provided views of great beauty and historical importance. One of Lane’s finest harbor depictions appears to be unique in its viewpoint, with no other views related to it. The painting has been simply titled Gloucester Harbor, but its drawing, titled Looking Outward from Head of Harbor (in Lane’s own handwriting), is a precise description of the location. Today, this location is still called “Head of the Harbor," though its scenic beauty is greatly diminished.

All of the shoreline in the painting is related to a reviving fishing industry in mid-nineteenth-century Gloucester as the Inner Harbor’s shallow bottom became increasingly problematic to merchants in the foreign trade, whose ever-larger ships needed wharfage in a deeper harbor. The Head of the Harbor became the last part to accommodate fishing vessels which, being smaller, were less hampered by the inconvenience and accepted groundings at low tide as part of doing business.

![]()

Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23)

The foreground illustrates common uses of the intertidal zone at low tide:

1. A dory—then a boat used in the shore fisheries (dory trawling using long lines was only being introduced to American fishermen at this time)—is being readied for the day’s work. Not enough gear is present to tell what that work will be. Lobstering, working fish traps and gillnets, and hand-line fishing were the most common types of dory fishing.

2. The two logs being hauled ashore are possibly for spars (finished masts were commonly delivered this way). More likely, they will be used as wharf spiles (pilings), either for a new wharf or as replacements for old, worm-eaten spiles.

3. A yawl boat is having its bottom seams payed with hot pitch, following the stripping and replacement of old caulking. Note the basket of caulking tools to the left of the boat.

4. Hot pitch for paying bottom seams is simmering in the kettle while the caulker’s assistant splits firewood.

5. A sloop-load of granite blocks has been off-loaded on the shore in preparation for building a new wharf or bulkhead pier. These blocks are so irregular in shape because they were probably split to size from field stones or quarry tailings. They are most likely intended for building a cob wharf, examples of which can be seen in this painting.

Although the painting shows this area in an early stage of development, there are several wharves lining the shore whose owners can be identified, many of them in the early years of long and successful careers:

6. Marchant’s Wharf is a fine example of a crib wharf, built up in layers called cribs, which were also used to frame the foundations of cob wharves. Both types of wharf construction are centuries old, many examples of which have survived to the present, though often concealed by subsequent “improvements.”

7. The adjoining flake yard’s waterfront is retained by a bulkhead pier of typical cob wharf construction. The siding is rubble stone, some of which has been split to form flat sides and then pieced together in an irregular pattern. The top is capped by a timber deck, with vertical spiles serving as supports for the stone siding. The horizontal structures atop the pier are fish flakes—wooden racks on which split salt cod were laid out to dry.

8. William Parkhurst’s wharf is another cob wharf (in the form of a finger pier) with a timber deck extension supported by spiles.

9. This barren unnamed shoreline obscures the oldest part of the East Gloucester community, whose houses rise behind it. Around its far end are the wharf of Benjamin Parsons & Co. and a complex of wharves, buildings, and a flake yard belonging to Samuel Wonson, whose family was one of the leading names in Gloucester’s fishing industry.

10. Five Pound Island was so named in colonial times for sheep pounds to keep rams when not needed for breeding. In Lane’s time, it had fish shacks and a flake yard.

11. Rocky Neck saw little use by the fishing industry until after a marine railway for repair and maintenance of fishing vessels was built at its northeast end in 1886.

12. Ten Pound Island was named, as Five Pound Island was, for sheep pounds, not for a supposed sum paid to Native Americans by early settlers. The lighthouse was first activated in 1821.

13. Frederick G. Low’s wharf at the head of Duncan’s Point. To the left of it is Harbor Rock with a wooden platform on top.

14. Wharf and fish house of S. W. Brown.

15. Wharf of George Friend & Co.

16. Wharf of George Parkhurst.

Two vessels—one afloat, the other aground—are of particular note:

17. A small example of a Georges Bank hand-line schooner, probably no more than fifty-five feet long, not counting spars, and drawing about seven feet. Her situation clearly shows the low-tide depth problem at this end of the Inner Harbor.

18. A merchant brig is in the process of clewing-up and furling sail as she comes to anchor off the southwest side of Ten Pound Island. In that area, there is adequate depth for anchorage about 650 feet from shore at low tide.

– Erik Ronnberg

Historical Materials

Oil on canvas

28 1/2 x 41 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Estate of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1949 (1332.20)

Detail showing yawl boat having its bottom seams payed with pitch.

Filed under: Yawl Boat »

1903 Four-page letter Collection of the Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

"[The painting] is offered you for $150 on as long time and in as many notes at 3% interest as you choose. . . I believe this to be the only important painting of Gloucester Harbor that Lane never duplicated. . . .Returning from a Gloucester visit while I was still under the roof there, father brought a print of Lane's first Gloucester view, bought of the artist at his Tremont Temple studio in Boston. An extra dollar had been paid for coloring it. For a few years it was a home delight.. . .I had been a few years in Gloucester when Lane began to come, for part of the time a while, if I remember rightly. He painted in his brother's house, "up in town" it then was. I recall visits there to see his pictures. But it was long after, that I could claim more than a simple speaking acquaintance. The Stacys were very kind, aiding him as time went on in selling paintings by lot. I invested in a view of Gloucester from Rocky Neck, thus put on sale at the old reading room, irreverently called "Wisdom Hall." And they bought direct of him to some extent, before other residents. Lane was much my senior and yet we gradually drifted together. Our earliest approach to friendship was after his abode began in Elm Street as an occupant of the old Prentiss [sic-corrected Stacy] house, moved there from Pleasant. I was a frequenter of this studio to a considerable extent, yet little compared with my intimacy at the next and last in the new stone house on the hill. Lane's art books and magazines were always at my service and a great inspiration and delight—notably the London Art Journal to which he long subscribed. I have here a little story to tell you. A Castine man came to Gloucester on business that brought the passing of $60 through my hands at 2 1/2 % commission. I bought with the $1.50 thus earned Ruskin's Modern Painters, my first purchase of an artbook. I dare say no other copy was then owned in town. . . .Lane was frequently in Boston, his sales agent being Balch who was at the head of his guild in those days. So in my Boston visits – I was led to Balch's fairly often – the resort of many artists and the depot of their works. Thus through, Lane in various ways I was long in touch with the art world, not only of New England but of New York and Philadelphia. I knew of most picture exhibits and saw many. The coming of the Dusseldorf Gallery to Boston was an event to fix itself in one's memory for all time. What talks of all these things Lane and I had in his studio and by my fireside!

For a long series of years I knew nearly every painting he made. I was with him on several trips to the Maine coast where he did much sketching, and sometimes was was [sic] his chooser of spots and bearer of materials when he sketched in the home neighborhood. Thus there are many paintings whose growth I saw both from brush and pencil. For his physical infirmity prevented his becoming an out-door colorist."

In the days prior mechanical refrigeration, salting and drying were the most common methods of preserving fish. Split cod were spread out on wooden racks, called "fish flakes," to dry. Drying time could take days, depending on weather and temperature. Warm, sunny weather could speed up the drying time, but also "burn" the fish, spoiling its texture and flavor. To prevent this, canvas awnings were stretched over wooden frames built onto the flakes. In wet weather, wooden boxes were placed over the flakes to protect them.

There were several large flake yards in Gloucester in Lane's day. One was situated between Battery Street and the beach, on the long point of land leading to the Fort, and is clearly shown in the 1851 Walling map.

c.1900.

Also filed under: Drying Fish »

Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing » // Drying Fish » // Historic Photographs »

1851 44 x 34 in. Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

1834–35 24 x 38 in. Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map is especially helpful in showing the wharves of the inner harbor at the foot of Washington Street.

24 x 38 in.

Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map is especially useful in showing the Fort.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Pavilion (Publick) Beach » // Town / Public Landings »

Wood drying racks, metal split salt fish. Scale: ½" = 1' (1:24)

Original diorama components made, 1892; replacements made 1993.

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce, 1925 (2014.071)

Fish flakes are wood drying racks for salt codfish, and have been used for this purpose in America since colonial times.

Also filed under: Drying Fish »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Maps »

In the 1850s, Captain Frederick G. Low owned fully one-third of the land comprising Duncan's point, including the lot purchased by Lane for his home and studio. Much of his property fronted the Inner Harbor, including two wharves in Harbor Cove and a third jutting southeast from the point toward Harbor Rock (see Walling & Hanson map below.)

Low's wharves are not conspicuous in any of Lane's depictions of Gloucester Harbor, which is ironic because many of his harbor scenes were sketched from Low's property. In The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester (Harbor Scene), 1848 (inv. 58), his wharf adjacent to the Collins estate wharf is obscured by a building on the Collins wharf and a ship tied up to his own wharf. In Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), his wharf extending to Harbor Rock is concealed by the rocks off Fort Point with only a bark to mark the head of the wharf to which it is tied up.

Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14), depicting the town from Rocky Neck, is the only painting which shows the shore line where Lowe's wharves were located (or to be located, given the early, 1844, date of this work). Lane's lithograph of 1846 (View of Gloucester, (From Rocky Neck), 1846 (inv. 57)) is similarly problematic, and his 1859 version () shows so many changes that the earlier wharves are no longer discernible.

– Erik Ronnberg

Watercolor on paper

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Maps » // Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

1851 44 x 34 in. Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

1834–35 Lithograph 24 x 38 in. Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map shows the location of F. E. Low's wharf and the ropewalk. Duncan's Point, the site where Lane would eventually build his studio, is also marked.

The later notes on the map are believed to be by Mason.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Residences » // Ropewalk » // Somes, Capt. John »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Low's, Rogers', and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

Five Pound Island lies in the middle of the deepest recess of Gloucester’s Inner Harbor, called the Head of the Harbor. It is now buried under the pilings of the State Pier which in 1937 was built out from the shore and over the island to provide modern scale dockage and freezer facilities for the fishing fleet.

In colonial days it was an undistinguished rock with very little vegetation that was likely named for the five sheep pounds (pens) holding rams on it, functioning as a smaller version of Ten Pound Island farther out in the harbor. In Lane’s time it had a few wharves and fishing shacks on it, but being disconnected from land it was not a very practical business location.

The island is shown in numerous Lane paintings, perhaps most prominently in Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23) where it lies at the center of the stage set of the Inner Harbor which Lane has ringed with activity both onshore and off.

Glass plate negative from Benham Collection

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View of Gloucester Harbor from Friend Street Wharves, Five Pound Island segment at far left, Rocky Neck, Eastern Point and Ten Pound Island in background.

Also filed under: Eastern Point » // Gloucester – City Views »

1851 44 x 34 in. Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Flake Yard » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Five Pound Island and Gloucester inner harbor taken from the top of Hammond Street building signs in foreground are for Severance, Carpenter and Crane, and Cooper at Clay Cove.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

The northeast quarter of Gloucester Harbor is an inlet bounded by Fort Point and Rocky Neck at its entrance. It is further indented by three coves: Harbor Cove and Vincent’s Cove on its north side, and Smith’s Cove on its south side. The shallow northeast end is called Head of the Harbor. Collectively, this inlet with its coves and shallows is called Inner Harbor.

The entrance to Inner Harbor is a wide channel bounded by Fort Point and Duncan’s Point on its north side, and by Rocky Neck on its south side. From colonial times to the late nineteenth century, it was popularly known as “the Stream” and served as anchorage for deeply loaded vessels for “lightering” (partial off-loading). Subsequently it was known as “Deep Hole.”

Of Inner Harbor’s three coves, Harbor Cove (sometimes called “Old Harbor” in later years) was the deepest and most heavily used by fishing vessels in the Colonial Period, and largely dominated by the foreign trade in the first half of the nineteenth century. Its shallow bottom was the undoing of the foreign trade, as larger vessels became too deep to approach its wharves, and the cove returned to servicing a growing fishing fleet in the 1850s.

Vincent’s Cove, a smaller neighbor to Harbor Cove, was bare ground at low tide, and mostly useless for wharfage. Its shoreline was well suited for shipbuilding, and the cove was deep enough at high tide for launching. Records of shipbuilding there prior to the early 1860s have to date not been found.Smith’s Cove afforded wharfage for fishing vessels at its east entrance, as seen in Lane’s lithograph View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass., 1836 (inv. 86). The rest of the cove saw little use until the expansion of the fisheries after 1865.

The Head of the Harbor begins at the shallows surrounding Five Pound Island, extending to the harbor’s northeast end. Lane’s depiction of this area in Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23) shows the problems faced by vessel owners at low tide. Despite the absence of deep water, this area saw rapid development after 1865 when a thriving fishing industry needed waterfront facilities, even if they were accessible only at high tide.

– Erik Ronnberg

c.1870 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

1876 Photograph Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

1851 44 x 34 in. Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Printer. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Baptist Church (Old, First, 1830) (Pleasant Street) » // Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Duncan's Point » // Five Pound Island » // Flake Yard » // Harbor Methodist Church (Prospect Street) » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Pavilion Hotel » // Procter Brothers » // Ropewalk » // Vincent's Cove » // Western Shore »

4 x 6 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Benham Collection

George Steele sail loft, William Jones spar yard, visible across harbor. Photograph is taken from high point on the Fort, overlooking business buildings on the Harbor Cove side.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Town House » // Universalist Church (Middle and Church Streets) » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

1834–35 Lithograph 24 x 38 in. Gloucester City Archives

"Drawn on a scale of one hundred feet to an inch. By John Mason 1834–45 from Actual Survey showing every Lott and building then standing on them giving the actual size of the buildings and width of the streets from the Canal to the head of the Harbour & part of Eastern point as farr as Smith's Cove and the Shore of the same with all the wharfs then in use. Gloucester Harbor 1834–35."

This map shows the location of F. E. Low's wharf and the ropewalk. Duncan's Point, the site where Lane would eventually build his studio, is also marked.

The later notes on the map are believed to be by Mason.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Low, Capt. Frederick Gilman » // Maps » // Mason, John » // Residences » // Ropewalk » // Somes, Capt. John »

44 x 34 in.

Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Segment of Harbor Village portion of map showing Collins' and other wharves in the Inner Harbor.

Also filed under: Graving Beach »

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

View related catalogue entries (2) »

Also filed under: Dolliver's Neck » // Fresh Water Cove » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Maps »

1865 41 x 29 inches Courtesy of the Massachusetts Archives Maps and Plans, Third Series Maps, v.66:p.1, no. 2352, SC1/series 50X

.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Collins's, William (estate wharf) » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves »

Photograph in The Illustrated Coast Pilot with Sailing Directions. The Coast of New England from New York to Eastport, Maine including Bays and Harbors, published by N. L. Stebbins, Boston

Also filed under: Beacons / Monuments / Spindles »

Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

c.1870s Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

From East Gloucester looking towards Gloucester.

Also filed under: Gloucester – City Views » // Historic Photographs »

1876 Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Stereo view showing Gloucester Harbor after a heavy snowfall

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Five Pound Island and Gloucester inner harbor taken from the top of Hammond Street building signs in foreground are for Severance, Carpenter and Crane, and Cooper at Clay Cove.

Also filed under: Five Pound Island »

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Schooner (Fishing) »

Oil on canvas

34 x 45 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Mrs. Jane Parker Stacy (Mrs. George O. Stacy),1948 (1289.1a)

Detail of party boat.

Also filed under: Party Boat »

c.1869 Glass plate negative Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive Detail from CAHA#00279

The magnificent views of Gloucester Harbor and the islands from the top floor of the stone house at Duncan's Point where Lane had his studio were the inspiration for many of his paintings.

From Buck and Dunlop, Fitz Henry Lane: Family, and Friends, pp. 59–74.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Lane's Stone House, Duncan's Point » // Residences »

Glass plate negative

3 x 4 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

#10112

Also filed under: Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky »

1876 Photograph Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

1860 In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860) Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related catalogue entries (4) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) » // Ten Pound Island »

These rocks were located in Gloucester's Inner Harbor, just off of Frederick Low's wharf on Duncan's Point. To keep boats from crashing into them, a small wooden structure, or dock, was built over the rocks.

Rocky Neck lies on the eastern side of Gloucester’s Inner Harbor and along with Ten Pound Island provides a vital block to the southerly and westerly seas running down the Outer Harbor. Called Peter Mud’s Neck in the late 1600s, it was an island at high tide until the 1830s, reachable only by walking over the sand bar connecting it to the mainland at low tide. When the stone causeway was put in in the 1830s it not only made the Rocky Neck a functional neighborhood of East Gloucester, it secured the southwest end of Smith’s Cove against swell from the Outer Harbor and made the cove a tight and secure anchorage.

In Lane’s time it was primarily sheep pasture with a small population living on the fringes. In 1859 a marine railway was built at the end of the neck which is still in operation. As a result of Gloucester’s burgeoning fish trade, wharves and fish businesses quickly sprang up along the shore of the newly secure Smith’s Cove. In 1863 another landmark Gloucester business, the marine antifouling copper paint manufactory of Tarr and Wonson was built on the western tip. The Hopper-esque dark red building still stands and guards the entrance to the Inner Harbor directly across from Fort Point.

Lane drew the view for his second and third Gloucester lithographs from Rocky Neck looking across to the Inner Harbor to the town. He also did a major painting Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844 (inv. 14) which shows the sheep, shepherd and dog on the rocky pasture in the foreground with the busy harbor and town unfolding before them.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Rocky Neck became an active waterfront neighborhood with a row of grand houses on its spine overlooking the harbor and town. Edward Hopper painted one of the more spectacular Beaux Arts houses on that ridge, the afternoon light catching its extraordinary trim and mansard roof, still beautifully preserved today.

Rocky Neck is perhaps best known today as Gloucester’s, and arguably America’s, most famous art colony. Beginning in the 1880’s and extending through the 1970’s, multiple generations of artists, including Homer, Duveneck, Hopper, Sloan, Twachtman and many others, representing every artistic style, have summered and worked, socialized and relaxed in the quaint and once ramshackle confines of the Neck.

c.1870 Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

c.1870 Stereograph card Procter Brothers, Publisher Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

Newspaper clipping in "Authors and Artists "scrapbook

p.42

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This painting was considered by far the best of the several paintings by Fitz H. Lane and was a view of Gloucester from Rocky Neck at the time Mr. Lane painted it in 1856. From this painting Mr. Lane had finished a number of lithographs which were sold at a very low price. This did not bring to Mr. Lane much ready money and he was somewhat disappointed so he mounted several of these on canvas, painted them in oil and sold them to several of his friends for $25 and there are a number of these at present held in Gloucester and valued very highly.

The original painting was given to the town about the time the new town house was built and was put on the wall back of the stage in the large hall. When the building was found to be on fire it was impossible to get into the big hall to save anything and so this picture was destroyed. It was a genuine regret that this happened because of its historic value and being considered as the best work that Mr. Lane had done. A study of the pictures finished by Mr. Lane from this original is very interesting and particularly by reason of the type of fishing vessel and shipping in the harbor. In the foreground of the painting is a fine type of the Surinamers of those days which sailed out of Gloucester and brought wealth to many Gloucester families.

Ten Pound Island guards the entrance to Gloucester’s Inner Harbor and provides a crucial block to heavy seas running southerly down the Outer Harbor from the open ocean beyond. The rocky island and its welcoming lighthouse is seen, passed, and possibly blessed by every mariner entering the safety of Gloucester’s Inner Harbor after outrunning a storm at sea. Ten Pound Island is situated such that the Inner Harbor is protected from open water on all sides making it one of the safest harbors in all New England.

Legend has it that the island was named for the ten pound sum paid to the Indians for the island, and the smaller Five Pound Island deeper in the Inner Harbor was purchased for that lesser sum. None of it makes much financial sense when the entirety of Cape Ann was purchased for only seven pounds from the Indian Samuel English, grandson of Masshanomett the Sagamore of Agawam in 1700. From approximately 1640 on the island was used to hold rams, and anyone putting female sheep on the island was fined. Gloucester historian Joseph Garland has posited that the name actually came from the number of sheep pens it held, or pounds as they were called, and the smaller Five Pound Island was similarly named.

The island itself is only a few acres of rock and struggling vegetation but is central to the marine life of the harbor as it defines the eastern edge of the deep channel used to turn the corner and enter the Inner Harbor. The first lighthouse was lit there in 1821, and a house was built for the keeper adjacent to the lighthouse.

In the summer of 1880 Winslow Homer boarded with the lighthouse keeper and painted some of his most masterful and evocative watercolor views of the busy harbor life swirling about the island at all times of day. Boys rowing dories, schooners tacking in and out in all weather, pleasure craft drifting in becalmed water, seen together they tell a Gloucester story of light, water and sail much as Lane’s work did only several decades earlier.

Colored lithograph

Cape Ann Museum Library and Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light »

Photograph

From The Illustrated Coast Pilot with Sailing Directions. The Coast of New England from New York to Eastport, Maine including Bays and Harbors, N. L. Stebbins, 1891.

Also filed under: Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light »

Oil on canvas

22 x 36 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., deposited by the Collection of Addison Gilbert Hospital, 1978 (DEP. 201)

Detail of party boat.

Also filed under: Party Boat »

Engraving of 1819 survey taken from American Coast Pilot 14th edition

9 1/2 x 8 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

D32 FF5

Also filed under: Dolliver's Neck » // Eastern Point » // Maps » // Norman's Woe »

Newspaper

Gloucester Telegraph

"By the will of the late Fitz H. Lane, Esq., his handsome painting of the Old Fort, Ten Pound Island, etc., now on exhibition at the rooms of the Gloucester Maritime Insurance Co., was given to the town... It will occupy its present position until the town has a suitable place to receive it."

Stereograph card

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View from top of Unitarian Church on Middle Street looking southeast, showing the Fort and Ten Pound Island. Tappan Block and Main Street buildings between Center and Hancock in foreground.

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Unitarian Church / First Parish Church (Middle Street) »

1860 In John J. Babson, History of the Town Gloucester (Gloucester, MA: Procter Brothers, 1860) Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

See p. 474.

View related catalogue entries (4) »

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester » // Chebacco Boat / Dogbody / Pinky » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Gloucester, Mass. - "Ten Pound Island Light » // Schooner (Coasting / Lumber / Topsail / Packet / Marsh Hay) »

Preceded by Annisquam as the earliest permanently settled harbor and Gloucester’s original first parish, Gloucester Harbor did not become a seaport of significance until the end of the 17th century. Its earliest fishing activity was focused on nearby grounds in the Gulf of Maine, few vessels venturing further to the banks off Canada. After 1700, as maritime activity was well-established in fishing, shipbuilding, and coastal trade, the waterfront saw the expansion of flake yards for drying fish and wharves for berthing and outfitting vessels, loading lumber and fish, and receiving trade goods. Shipbuilding was also carried on, using shorelines with straight slopes not suited for wharves.

By 1740, the majority of Cape Ann-owned vessels were berthed in Gloucester Harbor; three years later, Watch House Point (now called Fort Point) was armed and fortified. The fishing fleet continued to grow, numbering over 140 vessels by the time of the Revolution. A customs office was established in 1768, resulting in strong protests over seizures of contraband. Revolution brought hardship to the fishing industry, forcing many vessel owners to resort to privateering.

Independence saw a much-diminished fishing fleet and a severely impoverished seaport. With the Federally-sponsored incentive of the codfish bounties, Gloucester fishermen began to rebuild their fishing fleet. By 1790, trade with Surinam was under way, leading to the building and purchase of merchant vessels, new wharves, and improvements to old wharves in Harbor Cove, which had become Gloucester’s center of maritime activity. In addition to shipyards and sail lofts, two ropewalks furnished cordage for rigging.

The first four decades of the 19th century saw fitful growth in the fishing industry, due to the interruptions of war and financial panics. Few wharves were added to the waterfront in that period, and when new ones were built, their purpose was to serve the growing Surinam Trade. Fishing had come to its low point in the 1840s when the railroad reached Gloucester, opening a huge inland market for the fish it caught. The use of ice to keep fish fresh, combined with new and faster fishing schooners to get it quickly to port, sparked a revival in Gloucester’s fishing industry.

As Gloucester’s fishing industry revived, its growth in the Surinam Trade was hampered by its shallow harbor which made berthing of ever larger ships more difficult. Forced to seek a deeper harbor, merchants reluctantly sent their largest ships to Boston for unloading. Between 1850 and 1860, this process continued until ships and warehouses were relocated and their owners commuted to Boston by rail, leaving their old wharves to the fishing fleet. In 1863, the Surinam trade collapsed.

Gloucester’s fishing fleet grew dramatically in the 1850s for more reasons than ice, railroads, and faster schooners. The technology of catching fish also improved dramatically. Hand-line fishing (two hooks on a line) gave way to dory trawling with many hooks on a very long “trawl line,” while fishing for mackerel with hand-lines was replaced by “purse seining,” setting a 1,000-foot-long net in a circle around a school of mackerel. These dramatic improvements in productivity were expensive but made possible by the fishermen organizing a mutual savings bank to serve their needs and a mutual insurance company to cover their risks. These advantages could not be matched by any other fishing communities in New England or in the Canadian Maritime Provinces, sparking a huge migration of fishermen to Gloucester. These newcomers were welcomed to fill a growing work force while Gloucester’s native work force moved on to other, less dangerous, occupations.

Lane’s depictions of Gloucester’s waterfront best illustrate the period before 1850. After that date, his attention turned more to the Harbor’s outer shores, to nearby communities such as Manchester, to New York, back to Boston, and north to Maine. While his lapse of interest is regrettable, the scenes and activity he missed were becoming popular with photographers while his earlier waterfront views are nowhere else to be found.

–Erik Ronnberg

References:

Dates and happenings were based on (or confirmed by):

Mary Ray and Sarah V. Dunlap, “Gloucester, Massachusetts Historical Time-Line (Gloucester: Gloucester Archives Committee, 2002).

Improvements to Gloucester’s fishing technology, management, and financing are based on:

Wayne O’ Leary, “Maine Sea Fisheries” (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), pp. 166–179 (fishing technology), 235–251 (management and financing), and 235–251 (in-migration to Gloucester).

1876 Photograph Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) »

1876 Photograph Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Schooner (Fishing) » // Windmill »

44 x 34 in.

John Hanson, Publisher

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Low (Frederick G.) wharves » // Maps » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Town / Public Landings » // Windmill »

c.1875 Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This view of Gloucester's Inner Harbor shows three square-rigged vessels in the salt trade at anchor. The one at left is a (full-rigged) ship; the other two are barks. By the nature of their cargos, they were known as "salt ships" and "salt barks" respectively. Due to their draft (too deep to unload at wharfside) they were partially unloaded at anchor by "lighters" before being brought to the wharves for final unloading.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Bark / Barkentine or Demi-Bark » // Historic Photographs » // Salt »

1870s Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) »

1876 Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Stereo view showing Gloucester Harbor after a heavy snowfall

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs »

Wood, metal, and paint

20 1/4 x 10 1/4 x 10 1/2 in., scale: 1/2" = 1'

Made for the Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1892–93

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce

The wharf is built up of "cribs", square (sometimes rectangular) frames of logs, resembling a log cabin, but with spaces between crib layers that allow water to flow freely through the structure.Beams are laid over the top crib, on which the "deck" of the wharf is built. Vertical pilings (or "spiles" as locally known) are driven at intervals to serve as fenders where vessels are tied up.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Cob / Crib Wharf »

Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs »

c.1870 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Schooner (Fishing) »

In general, brigs were small to medium size merchant vessels, generally ranging between 80 and 120 feet in hull length. Their hull forms ranged from sharp-ended (for greater speed; see Brig "Antelope" in Boston Harbor, 1863 (inv. 43)) to “kettle-bottom” (a contemporary term for full-ended with wide hull bottom for maximum cargo capacity; see Ships in Ice off Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 44) and Boston Harbor, c.1850 (inv. 48)). The former were widely used in the packet trade (coastwise or transoceanic); the latter were bulk-carriers designed for long passages on regular routes. (1) This rig was favored by Gloucester merchants in the Surinam Trade, which led to vessels so-rigged being referred to by recent historians as Surinam brigs (see Brig "Cadet" in Gloucester Harbor, late 1840s (inv. 13) and Gloucester Harbor at Dusk, c.1852 (inv. 563)). (2)

Brigs are two-masted square-rigged vessels which fall into three categories:

Full-rigged brigs—simply called brigs—were fully square-rigged on both masts. A sub-type—called a snow—had a trysail mast on the aft side of the lower main mast, on which the spanker, with its gaff and boom, was set. (3)

Brigantines were square-rigged on the fore mast, but set only square topsails on the main mast. This type was rarely seen in America in Lane’s time, but was still used for some naval vessels and European merchant vessels. The term is commonly misapplied to hermaphrodite brigs. (4)

Hermaphrodite brigs—more commonly called half-brigs by American seamen and merchants—were square-rigged only on the fore mast, the main mast being rigged with a spanker and a gaff-topsail. Staysails were often set between the fore and main masts, there being no gaff-rigged sail on the fore mast.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 64–68.

2. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester Recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 62–74. A candid and witty view of Gloucester’s Surinam Trade, which employed brigs and barks.

3. R[ichard] H[enry] Dana, Jr., The Seaman's Friend (Boston: Thomas Groom & Co., 1841. 13th ed., 1873), 100 and Plate 4 and captions; and M.H. Parry, et al., Aak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World's Watercraft (Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 95.

4. Parry, 95, see Definition 1.

Oil on canvas

17 1/4 x 25 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Isabel Babson Lane, 1946 (1147.a)

Photo: Cape Ann Museum

Detail of brig "Cadet."

Also filed under: "Cadet" (Brig) »

Painting on board

72 x 48 in.

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

Chart showing the voyage of the brig Cadet to Surinam and return, March 10–June 11, 1840.

Also filed under: "Cadet" (Brig) » // Surinam Trade »

Schooners in Lane’s time were, with few exceptions, two-masted vessels carrying a fore-and-aft rig having one or two jibs, a fore staysail, gaff-rigged fore- and main sails, and often fore- and main topsails. One variant was the topsail schooner, which set a square topsail on the fore topmast. The hulls of both types were basically similar, their rigs having been chosen for sailing close to the wind. This was an advantage in the coastal trade, where entering confined ports required sailing into the wind and frequent tacking. The square topsail proved useful on longer coastwise voyages, the topsail providing a steadier motion in offshore swells, reducing wear and tear on canvas from the slatting of the fore-and-aft sails. (1)

Schooners of the types portrayed by Lane varied in size from 70 to 100 feet on deck. Their weight was never determined, and the term “tonnage” was a figure derived from a formula which assigned an approximation of hull volume for purposes of imposing duties (port taxes) oncargoes and other official levies. (2)

Crews of smaller schooners numbered three or four men. Larger schooners might carry four to six if a lengthy voyage was planned. The relative simplicity of the rig made sail handling much easier than on a square-rigged vessel. Schooner captains often owned shares in their vessels, but most schooners were majority-owned by land-based firms or by individuals who had the time and business connections to manage the tasks of acquiring and distributing the goods to be carried. (3)

Many schooners were informally “classified” by the nature of their work or the cargoes they carried, the terminology coined by their owners, agents, and crews—even sometimes by casual bystanders. In Lane’s lifetime, the following terms were commonly used for the schooner types he portrayed:

Fishing Schooners: While the port of Gloucester is synonymous with fishing and the schooner rig, Lane depicted only a few examples of fishing schooners in a Gloucester setting. Lane’s early years coincided with the preeminence of Gloucester’s foreign trade, which dominated the harbor while fishing was carried on from other Cape Ann communities under far less prosperous conditions than later. Only by the early 1850s was there a re-ascendency of the fishing industry in Gloucester Harbor, documented in a few of Lane’s paintings and lithographs. Depictions of fishing schooners at sea and at work are likewise few. Only A Smart Blow, c.1856 (inv. 9), showing cod fishing on Georges Bank (4), and At the Fishing Grounds, 1851 (inv. 276), showing mackerel jigging on Georges Bank, are known examples. (5)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 258. While three-masted schooners were in use in Lane’s time, none have appeared in his surviving work; and Charles S. Morgan, “New England Coasting Schooners”, The American Neptune 23, no. 1 (DATE): 5–9, from an article which deals mostly with later and larger schooner types.

2. John Lyman, “Register Tonnage and its Measurement”, The American Neptune V, nos. 3–4 (DATE). American tonnage laws in force in Lane’s lifetime are discussed in no. 3, pp. 226–27 and no. 4, p. 322.

3. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789–1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944). Vessels whose shipping or fishing voyages included visits to foreign ports were required to register with the Federal Customs agent at their home port. While the vessel’s trade or work was unrecorded, their owners and master were listed, in addition to registry dimensions and place where built. Records kept by the National Archives can be consulted for information on specific voyages and ports visited.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 74–76.

5. Howard I. Chapelle, The American Fishing Schooners (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1973), 58–75, 76–101.

1852

Oil on canvas

28 x 48 1/2 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Deposited by the City of Gloucester, 1952. Given to the city by Mrs. Julian James in memory of her grandfather Sidney Mason, 1913 (DEP. 200)

Detail of fishing schooner.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove »

c.1865 Stereograph card Frank Rowell, Publisher stereo image, "x " on card, "x" Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

View showing a sharpshooter fishing schooner, circa 1850. Note the stern davits for a yawl boat, which is being towed astern in this view.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Model made for marine artist Thomas M. Hoyne

scale: 3/8" = 1'

Thomas M. Hoyne Collection, Mystic Seaport, Conn.

While this model was built to represent a typical Marblehead fishing schooner of the early nineteenth century, it has the basic characteristics of other banks fishing schooners of that region and period: a sharper bow below the waterline and a generally more sea-kindly hull form, a high quarter deck, and a yawl-boat on stern davits.

The simple schooner rig could be fitted with a fore topmast and square topsail for making winter trading voyages to the West Indies. The yawl boat was often put ashore and a "moses boat" shipped on the stern davits for bringing barrels of rum and molasses from a beach to the schooner.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seafarers in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 29–31.

Also filed under: Hand-lining » // Ship Models »

20 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive, Gloucester, Mass.

The image, as originally drafted, showed only spars and sail outlines with dimensions, and an approximate deck line. The hull is a complete overdrawing, in fine pencil lines with varied shading, all agreeing closely with Lane's drawing style and depiction of water. Fishing schooners very similar to this one can be seen in his painting /entry:240/.

– Erik Ronnberg

Newspaper

"Shipping Intelligence: Port of Gloucester"

"Fishermen . . . The T. [Tasso] was considerably injured by coming in contact with brig Deposite, at Salem . . ."

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Newsprint

From bound volume owned by publisher Francis Procter

Collection of Fred and Stephanie Buck

"A Prize Race—We have heard it intimated that some of our fishermen intend trying the merits of their "crack" schooners this fall, after the fishing season is done. Why not! . . .Such a fleet under full press of sail, would be worth going many a mile to witness; then for the witchery of Lane's matchless pencil to fix the scene upon canvass. . ."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Newspaper / Journal Articles »

Also filed under: Cape Ann Advertiser Masthead »

c.1870 Stereograph card Procter Brothers, Publisher Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, Looking Southwest. This gives a portion of the Harbor lying between Ten Pound Island and Eastern Point. At the time of taking this picture the wind was from the northeast, and a large fleet of fishing and other vessels were in the harbor. In the range of the picture about one hundred vessels were at anchor. In the small Cove in the foreground quite a number of dories are moored. Eastern Point appears on the left in the background."

Southeast Harbor was known for being a safe harbor.

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Outer » // Historic Photographs » // Rocky Neck » // Small Craft – Wherries, and Dories »

1870s Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Said schooner was captured about the first of September, 1871, by Capt. Torry, of the Dominion Cutter 'Sweepstakes,' for alleged violation of the Fishery Treaty. She was gallantly recaptured from the harbor of Guysboro, N.S., by Capt. Harvey Knowlton., Jr., (one of her owners,) assisted by six brave seamen, on Sunday night, Oct. 8th. The Dominion Government never asked for her return, and the United States Government very readily granted her a new set of papers."

Also filed under: Fishing » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

1876 Photograph Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

c.1870 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive (2013.068)

Schooner fleet anchored in the inner harbor. Looking east from Rocky Neck, Duncan's Point wharves and Lane house (at far left), Sawyer School cupola on Friend Street.

Also filed under: Duncan's Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Waterfront, Gloucester »

See p. 254.

As Erik Ronnberg has noted, Lane's engraving follows closely the French publication, Jal's "Glossaire Nautique" of 1848.

Also filed under: Babson History of the Town of Gloucester »

Wood, cordage, acrylic paste, metal

~40 in. x 30 in.

Erik Ronnberg

Model shows mast of fishing vessel being unstepped.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Fishing »

Watercolor on paper

8 3/4 x 19 3/4 in.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Rev. and Mrs. A. A. Madsen, 1950

Accession # 1468

Fishing schooners in Gloucester's outer harbor, probably riding out bad weather.

Also filed under: Elwell, D. Jerome » // Gloucester Harbor, Outer »

1876 Photograph Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Ignatius Weber's windmill (now defunct) is shown.

Also filed under: Flake Yard » // Fort (The) and Fort Point » // Gloucester Harbor, Inner / Harbor Cove » // Historic Photographs » // Rogers's (George H.) wharves » // Waterfront, Gloucester » // Windmill »

Print from bound volume of Gloucester scenes sent to the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

11 x 14 in.

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives

Schooner "Grace L. Fears" at David A. Story Yard in Vincent's Cove.

Also filed under: Historic Photographs » // Shipbuilding / Repair » // Vincent's Cove »

The yawl boat was a ninteenth-century development of earlier ships' boats built for naval and merchant use. Usually twenty feet long or less, they had round bottoms and square sterns; many had raking stem profiles. Yawl boats built for fishing tended to have greater beam than those built for vessels in the coastal trades. In the hand-line fisheries, where the crew fished from the schooner's rails, a single yawl boat was hung from the stern davits as a life boat or for use in port. Their possible use as lifeboats required greater breadth to provide room for the whole crew. In port, they carried crew, provisions, and gear between schooner and shore. (1)

Lane's most dramatic depictions of fishing schooners' yawl-boats are found in his paintings Gloucester Outer Harbor, from the Cut, 1850s (inv. 109) and /entry:311. Their hull forms follow closely that of Chapelle's lines drawing. (2) Similar examples appear in the foregrounds of Gloucester Harbor, 1852 (inv. 38), Ships in Ice off Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 44), and The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271). A slightly smaller example is having its bottom seams payed with pitch in the foreground of Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23). In Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), a grounded yawl boat gives an excellent view of its seating arrangement, while fishing schooners in the left background have yawl boats hung from their stern davits, or floating astern.

One remarkable drawing, Untitled, n.d. (inv. 219) illustrates both the hull geometry of a yawl boat and Lane's uncanny accuracy in depicting hull form in perspective. No hull construction other than plank seams is shown, leaving pure hull form to be explored, leading in turn to unanswered questions concerning Lane's training to achieve such understanding of naval architecture.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, American Small Sailing Craft (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1951), 222–23.

2. Ibid., 223.

Oil on canvas

12 1/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M.and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-1865 (48.447)

A schooner's yawl lies marooned in the ice-bound harbor in this detail.

The Ten Pound Island light was built on a three-and-a-half acre island at the eastern end of Gloucester Harbor. Built as a conical stone tower, the original 20-foot-tall Ten Pound Island Light was first lit in October, 1821 after the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Town of Gloucester ceded 1.7 acres to the U.S. Government for the construction of an inner harbor lighthouse to help mariners navigate the harbor. Ten Pound Island light was a popular subject with artists, including Winslow Homer, who boarded with the lighthouse keeper at Ten Pound Island in the summer of 1880. It is frequently featured in Lane's paintings of Gloucester Harbor.

This information has been shared with the Lane project by Jeremy D'Entremont. More information can be found at his website, www.newenglandlighthouses.net or in The Lighthouse Handbook New England. This information has also been summarized from Paul St. Germain's book, Lighthouses and Lifesaving Stations on Cape Ann.

Colored lithograph

Cape Ann Museum Library and Archive

Also filed under: Ten Pound Island »

Photograph

From The Illustrated Coast Pilot with Sailing Directions. The Coast of New England from New York to Eastport, Maine including Bays and Harbors, N. L. Stebbins, 1891.

Also filed under: Ten Pound Island »

The terms "cob wharf" and "crib wharf" refer to a common form of wharf construction dating from pre-colonial times in Europe to the early nineteenth century in America. Both utilize a rectangular frame of timber called a "crib," which forms the foundation of the timber-and-fill structure built over it.The Hamersly Naval Encyclopaedia defines a crib as "a structure of logs filled with stones, etc., and used as a dam, pier, ice-breaker, etc." A cob is defined as "a breakwater or dock made of piles and timber, and filled in with rocks. The vagueness of these definitions probably explains the interchange of these terms in contemporary descriptions. (1)

In Lane's paintings of Gloucester Harbor, we see what could be both examples of these wharf types on the point of land in Gloucester Harbor, 1847 (inv. 23) at far left. The wharf built up of layers of cribs (like a log cabin) fits the definition of a crib wharf, while the wharf beyond it with vertical pilings enclosing exposed stone would be a cob wharf. Going by this observation, other examples of cob wharves can be found in the depictions of Harbor Cove from the 1840s in The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 28), The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), and The Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847 (inv. 271).

Going by the Hamersly definition of cob wharf, coupled with recent archeological studies of Boston's old waterfront, this constuction was used for both finger piers and bulkhead piers in Gloucester Harbor. Thus, the bukhead piers adjoining and linking the wharves on Fort Point were cob wharves, their stone fill appearing no different from that of the finger piers. (2)

The stone fill used in these wharves was rubble stone: beach stones, field stones, and boulders broken into irregular shapes. Shaped stone blocks of quarried granite do not appear in Lane's depictions of wharves until George H. Rogers began construction of his wharf on Fort Point as noted in Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 17) and Ten Pound Island in Gloucester Harbor, 1864 (inv. 104). The building of this wharf marks a clean break with older wharf construction in Gloucester's Harbor Cove.

– Erik Ronnberg

References::

1. A Naval Encyclopaedia (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884. Reprint: Detroit: Gale Research Co., 1971), 146,182.

2. Nancy S. Seasholes, Breaking Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003), 13–19.

Wood, metal, and paint

20 1/4 x 10 1/4 x 10 1/2 in., scale: 1/2" = 1'

Made for the Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1892–93

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce

The wharf is built up of "cribs", square (sometimes rectangular) frames of logs, resembling a log cabin, but with spaces between crib layers that allow water to flow freely through the structure.Beams are laid over the top crib, on which the "deck" of the wharf is built. Vertical pilings (or "spiles" as locally known) are driven at intervals to serve as fenders where vessels are tied up.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Waterfront, Gloucester »

The processing of dried salt cod (the most common form of salt fish) began after the hooked cod came on board and was put in a holding pen on deck until there was a large deck load or the day's fishing was done. At that time, the fish would be split, gutted (the livers were saved, the head removed, and the tongues and cheeks cut out). The split fish were placed in pens in the hold, carefully salted as they were stacked in layers. This initial salting kept them in good condition until they were landed at the fish pier.

After landing, each fish was carefully washed in a dory filled with sea water, removing much of the initial salting. They were then given a second salting, using a finer grade with fewer impurities. Then they were loaded onto a barrow or cart, and wheeled to the flake yard, where they were spread out on wooden racks, called "fish flakes," to dry. Drying time could take days, depending on weather and temperature. Warm, sunny weather could speed up the drying time, but also "burn" the fish, spoiling its texture and flavor. To prevent this, canvas awnings were stretched over wooden frames built onto the flakes.

Rain was also harmful to the fish, which were gathered in compact piles on the flakes and covered with up-turned wooden boxes until dry weather returned. Once dried, the fish were returned to the fish house and stored in a dry room, awaiting skinning, trimming, and packaging for the domestic market.

– Erik Ronnberg

c.1900.

Also filed under: Flake Yard »

Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing » // Flake Yard » // Historic Photographs »

Wood drying racks, metal split salt fish. Scale: ½" = 1' (1:24)

Original diorama components made, 1892; replacements made 1993.

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce, 1925 (2014.071)

Fish flakes are wood drying racks for salt codfish, and have been used for this purpose in America since colonial times.

Also filed under: Flake Yard »

In G. Brown Goode, The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office)

A vessel having returned from the fishing grounds with a fare of split salted cod, is discharging it at a fish pier for re-salting and drying. The fish are tossed from deck to wharf with sharp two-pronged gaffs, and from there to a large scale for weighing. From there, they will be taken to another part of the wharf for washing and re-salting.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing » // Fishing » // Georges Bank, Mass. »

New York Public Library

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing »

In G. Brown Goode The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office)

See pl. 35.

After landing and weighing, the cod are split and washed, a dory filled with water serving as the wash tub. Once thoroughly rinsed of the coarse first salting, the split cod are piled in the wharf shed where they will be re-salted, usually with a finer grade of salt, and stored in bins or large casks until ready for drying on the fish flakes.

– Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Cod / Cod Fishing »

Also filed under: Fishing »

5' 11" l. x 28" h. x 23" w. Wheel 20" d.

19th–early 20th century

Cape Ann Museum. Gift of the Gloucester Fishermen's Museum (2542)

Used to move salt fish in a flake yard. Barrows of this type were commonly used to carry a wide variety of materials around the waterfront.

Also filed under: Objects »

Fishing and commerce came late to Gloucester Harbor, other harbors on Cape Ann having been developed sooner for these purposes. The rich and varied stocks of fish in Ipswich Bay and off Sandy Bay made the coves and harbors of Cape Ann's northern and eastern shores more convenient for shore fishermen in colonial times. The early successful permanent settlements on Cape Ann were in Annisquam Harbor and along the Annisquam River, leading to the establishment of Cape Ann's First Parish in that area. (1)

Shipbuilding in Gloucester Harbor began in the mid-seventeenth century, and by its end had produced a sizeable fleet of vessels which were active in the Grand Banks fishery. By the early 18th century, Gloucester Harbor was a busy fishing port becoming the economic center of Cape Ann—a reality finally recognized in 1740, when the First Parish built a new meeting house at the harbor, officially confirming its leading role. (2)

Gloucester's fishing enterprise was fueled by a demand for fish in Europe and their colonies in the West Indies. Vessels shipping fish to Europe returned with domestic wares and materials unavailable locally. Shipments of dried fish of lower grades went to plantations in the West Indies to feed their slaves; return cargos were usually sugar, molasses, and fine hardwoods to be used for cabinetry. By the 19th century, this trade had extended to Surinam, where fine Dutch domestic wares were added to the imports list. The Surinam Trade became Gloucester's dominant maritime activity in the first half of the nineteenth century. (3)

Success in the Surinam Trade led to using ever larger vessels to carry the goods - a problem for a shallow harbor with no dredging facilities. This forced Gloucester shipowners to move their port facilities and offices to Boston; after 1850, very few Surinam goods were landed at Gloucester. This opened Harbor Cove (Gloucester's prime port facility) to the fishing industry, just as momentous changes were to take place in fishing technology. (4)

Improvements to fishing methods and gear, namely dory trawling and mackerel seining, dramatically improved catches of cod and mackerel—at a cost. The gear was expensive. Gloucester was in a unique position to take advantage of this gear, thanks to banks and insurance firms with strong interests in the industry, local manufacturers of the new fishing gear, and a steady influx of young men eager for the work. The post-Civil War years saw a rapid rebuilding of Gloucester's fishing industry which could not be matched by rival New England fishing ports. (5)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Mary Ray, and Sarah V. Dunlap, Gloucester, Massachusetts Historical Time-line, 1000–1999 (Gloucester, MA: Archives, 2002), 10–16.

2. Ibid., 12, 17, 20, 24–25, 27–28, 30.

3. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, Gloucester recollected: A Familiar History (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1974), 50–69.

4. Ibid.

5. Wayne M. O'Leary, Maine Sea Fisheries (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), 160–79.

Newspaper

Ad in Gloucester Telegraph

FISHING AND SAILING PARTIES

"Persons desirous of enjoying a SAILING or FISHING EXCURSION, are informed that the subscriber will be in readiness with the Boat EUREKA, to attend to all who may favor him with their patronage. JOHN J. FERSON"

Also filed under: Newspaper / Journal Articles » // Party Boat »

The harvesting of granite from quarries dug deep into the earth was an important industry on Cape Ann from the 1830s through the early 20th century. Second only to fishing in economic output, for 100 years the granite business played a pivotal role in the local economy providing jobs for many, turning profits for some and generating tons and tons of cut granite that was used here on Cape Ann and shipped to ports all along the Atlantic seaboard.

Granite quarrying started slowly in this area in the late eighteenth century with small operations peppered across the rocky terrain. Construction of a fort at Castle Island in Boston Harbor in 1798 followed by a jail in nearby Salem in 1813, jump-started the granite industry here on Cape Ann. During the 1830s and 1840s, the trade grew steadily. By the 1850s, the stone business was firmly established and Cape Ann granite was known throughout the region. So extensive and so awe-inspiring were operations during the second half of the nineteenth century some observers feared that the business might actually run out of stone.

While granite was taken from the earth in all different sizes and shapes, Cape Ann specialized in the conversion of that granite into paving blocks which were used to finish roads and streets. Millions of paving stones were shipped out of Cape Ann annually, destined for construction projects in New York, Philadelphia and all along the Atlantic seaboard. While paving blocks were basically uniform in size, there were subtle differences leading some to be referred to as Philadelphia blocks while others were identified as Boston blocks or Washington blocks.

– Martha Oaks (April, 2015)

c.1880 Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This view shows a wood derrick for hoisting granite blocks.

Also filed under: Eastern Point » // Historic Photographs »

Stereograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Historic Photographs »

Stereograph

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

Also filed under: Gundalow / Scow »

1851 44 x 34 in. Henry Francis Walling, Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Essex Co. Massachusetts. Philadelphia, A. Kollner, 1851 Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

"Map of the Towns of Gloucester and Rockport, Massachusetts. H.F. Walling, Civil Engineer. John Hanson, Publisher. 1851. Population of Gloucester in 1850 7,805. Population of Rockport in 1850 3,213."

Also filed under: Annisquam River » // Babson House » // Coffin's Beach » // Eastern Railroad » // Gloucester, Mass. – Annisquam Harbor Lighthouse » // Loaf, The » // Low (David) House » // Maps » // Old First Parish / Subsequent Fourth Parish Church (at the Green) » // Riverdale Methodist Church (Washington Street) » // White-Ellery House »

c.1880 Stereograph card Cape Ann Museum Library & Archive

This view shows a wood derrick for hoisting granite blocks.

Also filed under: Eastern Point » // Historic Photographs »

Painted wood

Scale: 1:16. Galamander shop, Vinalhaven, Maine.

Cape Ann Museum. Gift of Barbara Erkkila, 1997

In the nineteenth century granite was hauled from Cape Ann quarries on heavy carts called garymanders which were pulled by oxen or horses (known as "galamander" in Maine.) A boom rigged above the rear axle was used to hoist the stone so it could be held by chains beneath the wagon. The garymander oak wheels were eight feet high with iron rims made by a blacksmith.

Also filed under: Objects »

Cape Ann Museum (1994.65)

Oilcan originally owned by Frederickj "Rick" Larsen

Cape Ann Museum (1994.76.3)

Peen hammer originally owned by Johann Jacob Erkkila (1877–1939)

(Cape Ann Museum) 1994.76.23a

Heavy blacksmith's sledge owned by John Fuge (1873–1967)

Cape Ann Museum (1997.24.0)

Although from a later period, these tools are similar to tools used in Lane's time.

Also filed under: Objects »

Photograph

Private collection

Granite scow being unloaded at Knowlton's Point, Sandy Bay. Sandy Bay Ledge visible in right background, Dodge's Rock in left background.

Also filed under: Gundalow / Scow »

Wood, metal, cordage, cloth, paint.

Scale: ¼ in. = 1ft. (1:48)

Cape Ann Museum. Gift of Roland and Martta Blanchet (1997.17.3)