An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

inv. 47

Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine

1862 Oil on canvas 15 3/4 x 26 1/8 in. (40 x 66.4 cm) Inscribed and dated verso (prior to relining): Owl's Head – Penobscot Bay, by F.H. Lane, 1862

|

Related Work in the Catalog

Explore catalog entries by keywords view all keywords »

Historical Materials

Below is historical information related to the Lane work above. To see complete information on a subject on the Historical Materials page, click on the subject name (in bold and underlined).

The Camden Mountains, also called the Camden Hills, are located just northeast of the town of Camden. The range includes Mount Megunticook, upon whose shoulders Mount Battie sits, Cameron Mountain, and Bald Rock Mountain. They stand high above West Penobscot Bay between Camden and Lincolnville, looking east toward Mount Desert and the rising sun. The Wabenaki, loosely defined as the "people of the dawn," greeted their maritime world, "the dawn land," from the Camden Hills, and other high points, including Mount Wallamatogus in Penobscot (460 feet), Awan-adjo (at Bluehill), Caterpillar Hill in Sedgwick (with its panoramic sweep which stretches from the Camden Hills to Mount Desert and far out into Penobscot Bay), and atop Cadillac Mountain, Mount Desert. It is from the same peaks that artists and pilgrims alike still climb to view Penobscot Bay.

Mad-kam-ig-os'-sek, "big high land," is the Wabenaki word for Camden, and Meg-un-ti-cook, "big mountain harbor," the name for the harbor, is now used for Mount Megunticook. The inner harbor, quiet and safe, would have been the ideal place for a large, oceangoing canoe to lay up when the sea was rough. Capt. John Smith visited this place in 1614, during the Beaver Wars, and noted that the high mountains were used as a refuge from the Mik'maq of the Maritimes who fought the Wabenaki of Penobscot Bay to maintain their place as middlemen in the fur trade. These raiders would travel along the Downeast coast in their shallops. Mount Battie, of many spellings, was noted as Mount Betty in documents dating from 1757. It is a European corruption of a word borrowed from another place, the Madambettox Hills of Rockland.

-Mark Honey

References:

Eckstorm, Fannie Hardy, "Indian Place-Names of the Penobscot Valley and the Maine Coast," University of Maine Studies, 2nd Series, #55, November 1941, reprinted 1960 by the University of Maine Press. DeLorme's Atlas. Frank G Speck's "Penobscot Man," University Of Pennsylvania Press, 1940.

Newsprint

Gloucester Telegraph

"The Reef of Norman's Woe ... is now commemorated in painting too, one of the finest pictures from Lane's easel. ... The sketch was made at the pretty spot commonly called, we believe, Master Moore's Cove. Being some little way off the main track to Rafe's Chasm, it is seldom visited, except by the more inquisitive lovers of nature who leave the beaten road to pry out such pleasant places. ... We wish it might find a home buyer, rather than go off to enrich another community." Flowery description follows, then "There is another and larger work in the artist's studio, which, happily, is to be retained. It received much well deserved notice and commendation. The subject is a view southward from the 'Cut,' with the picturesque promontory commonly known as 'Stage Fort,' and historically interesting as the supposed spot of the 'Landing at Cape Ann' in the middle distance, and Eastern Point on the extreme left." More description follows, "Among other attractions of the studio, and particularly worthy of mention, is a cabinet picture with an effect similar to the Norman's Woe. The subject is chosen from the many sketches of the grand scenery of the Maine sea-coast with which the artist's portfolio is rich. It is a view of the Camden mountains sketches from the Graves, a jagged ledge far out in the bay, which is accessible in only the smoothest water."

Also filed under: Cut, The (Stacy Blvd.) » // Newspaper / Journal Articles » // The Graves »

Owls Head is a peninsula that extends into West Penobscot Bay south of Rockland. Owls Head Light also marks the point where the Muscle Ridge Channel opens into West Penobscot Bay. (Muscle may have originally been Mussle).

Owls Head Light guides mariners into the port of Rockland and her ravenous lime kilns. Monroe Island, off Owls Head, has been a landmark for navigators from the age of Champlain, and the lee has provided shelter for mariners throughout the ages, "Owls Head Harbor may well have been the most frequented transient anchorage in the entire Penobscot region until well into the 19th century." "Five Hundred sail have been passing Owl's Head in one day," a mariner writes in the 1850s." Among the many legends of Owls Head was the scalping of 2 Indians by colonial forces led by Capt. Joseph Fox in 1757.

– Mark Honey

References:

Bill Caldwell, Lighthouses of Maine (Portland, ME: Gannett Books, 1986).

Roger F. Duncan, Coastal Maine: A Maritime History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1992).

Charles B. McLane, and Carol Evarts McLane, Islands of the Mid-Maine Coast: Penobscot Bay, vol. 1, rev. ed. (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House Publishers; in association with the Island Institute, Rockland, ME),120–22.

William Hutchinson Rowe, The Maritime History of Maine: Three Centuries of Shipbuilding & Seafaring (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1948).

Letter

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

Thanks for "View of Owl's Head", a moonlight scene: "Mr. Lane, Dear Sir, when I expressed to you, during your visit to us, the last summer, my admiration of moonlight scenes, I did not for a moment suppose that I should ever become the possessor of one, and that so beautiful as "The View of Owls Head," which you have so kindly, and in so delicate a manner presented to me, and for which, I now beg you to accept my heartfelt thanks, also, be assured, if your pleasure in giving has been half equal to mine in receiving, you have been amply repaid for your kindness, and I alone, am the debtor. . . ."

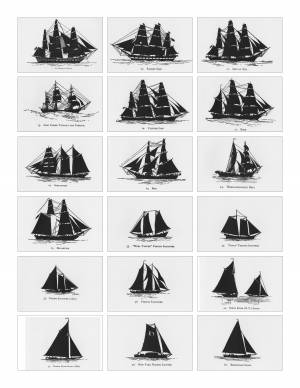

Hermaphrodite brigs—more commonly called half-brigs by American seamen and merchants—were square-rigged only on the fore mast, the main mast being rigged with a spanker and a gaff-topsail. Staysails were often set between the fore and main masts, there being no gaff-rigged sail on the fore mast. (1)

The half-brig was the most common brig type used in the coasting trade and appears often in Lane’s coastal and harbor scenes. The type was further identified by the cargo it carried, if it was conspicuously limited to a specialized trade. Lumber brigs (see Shipping in Down East Waters, 1854 (inv. 212) and View of Southwest Harbor, Maine: Entrance to Somes Sound, 1852 (inv. 260)) and hay brigs (see Lighthouse at Camden, Maine, 1851 (inv. 320)) were recognizable by their conspicuous deck loads. Whaling brigs were easily distinguished by their whaleboats carried on side davits (see Ships in the Harbor (not published)). (2)

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. M.H. Parry, et al., Aaak to Zumbra: A Dictionary of the World's Watercraft Newport News, VA: The Mariners’ Museum, 2000), 268, 274; and A Naval Encyclopaedia (L.R. Hamersly & Co., 1884. Reprint: Detroit, MI: Gale Research Company, 1971), 93, under "Brig-schooner."

2. W.H. Bunting, An Eye for the Coast (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House: 1998), 52–54, 68–69; and W.H. Bunting, A Day's Work, part 1 (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House: 1997), 52.

Schooners in Lane’s time were, with few exceptions, two-masted vessels carrying a fore-and-aft rig having one or two jibs, a fore staysail, gaff-rigged fore- and main sails, and often fore- and main topsails. One variant was the topsail schooner, which set a square topsail on the fore topmast. The hulls of both types were basically similar, their rigs having been chosen for sailing close to the wind. This was an advantage in the coastal trade, where entering confined ports required sailing into the wind and frequent tacking. The square topsail proved useful on longer coastwise voyages, the topsail providing a steadier motion in offshore swells, reducing wear and tear on canvas from the slatting of the fore-and-aft sails. (1)

Schooners of the types portrayed by Lane varied in size from 70 to 100 feet on deck. Their weight was never determined, and the term “tonnage” was a figure derived from a formula which assigned an approximation of hull volume for purposes of imposing duties (port taxes) on cargoes and other official levies. (2)

Crews of smaller schooners numbered three or four men. Larger schooners might carry four to six if a lengthy voyage was planned. The relative simplicity of the rig made sail handling much easier than on a square-rigged vessel. Schooner captains often owned shares in their vessels, but most schooners were majority-owned by land-based firms or by individuals who had the time and business connections to manage the tasks of acquiring and distributing the goods to be carried. (3)

Many schooners were informally “classified” by the nature of their work or the cargoes they carried, the terminology coined by their owners, agents, and crews—even sometimes by casual bystanders. In Lane’s lifetime, the following terms were commonly used for the schooner types he portrayed:

Coasting schooners: This is the most general term, applied to any merchant schooner carrying cargo from one coastal port to another along the United States coast (see Bar Island and Mt. Desert Mountains from Somes Settlement, 1850 (inv. 401), right foreground). (4)

Packet schooners: Like packet sloops, these vessels carried passengers and various higher-value goods to and from specific ports on regular schedules. They were generally better-maintained and finished than schooners carrying bulk cargoes (see The Old Fort and Ten Pound Island, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 30), center; and Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850 (inv. 240), stern view). (5)

Lumber schooners: Built for the most common specialized trade of Lane’s time, they were fitted with bow ports for loading lumber in their holds (see View of Southwest Harbor, Maine: Entrance to Somes Sound, 1852 (inv. 260)) and carried large deck loads as well (Stage Rocks and the Western Shore of Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1857 (inv. 8), right). Lumber schooners intended for long coastal trips were often rigged with square topsails on their fore masts (see Becalmed Off Halfway Rock, 1860 (inv. 344), left; Maverick House, 1835 (not published); and Lumber Schooner in a Gale, 1863 (inv. 552)). (6)

Schooners in other specialized trades. Some coasting schooners built for carrying varied cargoes would be used for, or converted to, special trades. This was true in the stone trade where stone schooners (like stone sloops) would be adapted for carrying stone from quarries to a coastal destination. A Lane depiction of a stone schooner is yet to be found. Marsh hay was a priority cargo for gundalows operating around salt marshes, and it is likely that some coasting schooners made a specialty of transporting this necessity for horses to urban ports which relied heavily on horses for transportation needs. Lane depicted at least two examples of hay schooners (see Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 391), left; and Coasting Schooner off Boon Island, c.1850 (inv. 564)), their decks neatly piled high with bales of hay, well secured with rope and tarpaulins.

– Erik Ronnberg

References:

1. Howard I. Chapelle, The History of American Sailing Ships (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1935), 258. While three-masted schooners were in use in Lane’s time, none have appeared in his surviving work; and Charles S. Morgan, “New England Coasting Schooners”, The American Neptune 23, no. 1 (DATE): 5–9, from an article which deals mostly with later and larger schooner types.

2. John Lyman, “Register Tonnage and its Measurement”, The American Neptune V, nos. 3–4 (DATE). American tonnage laws in force in Lane’s lifetime are discussed in no. 3, pp. 226–27 and no. 4, p. 322.

3. Ship Registers of the District of Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1789–1875 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1944). Vessels whose shipping or fishing voyages included visits to foreign ports were required to register with the Federal Customs agent at their home port. While the vessel’s trade or work was unrecorded, their owners and master were listed, in addition to registry dimensions and place where built. Records kept by the National Archives can be consulted for information on specific voyages and ports visited.

4. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1960), 40, 42–43.

5. Ibid., 42–43, 73.

6. Ibid., 74–76.

A topsail schooner has no tops at her foremast, and is fore-and-aft rigged at her mainmast. She differs from an hermaphrodite brig in that she is not properly square-rigged at her foremast, having no top, and carrying a fore-and-aft foresail instead of a square foresail and a spencer.

Wood rails, metal rollers, chain; wood cradle. Scale: ½" = 1' (1:24)

Original diorama components made, 1892; replacements made, 1993.

Cape Ann Museum, from Gloucester Chamber of Commerce, 1925 (2014.071)

A schooner is shown hauled out on a cradle which travels over racks of rollers on a wood and metal track.

Also filed under: Burnham Brothers Marine Railway » // Marine Railways »

Glass plate negative

Collection of Erik Ronnberg

Also filed under: Lobstering »

Details about Maine's lumber trade in 1855, see pp. 250–52

Also filed under: Castine » // Lumber Industry »

The Owl's Head Light is situated at the entrance to Rockland Harbor, Maine and overlooks the western Penobscot Bay. The first Owl's Head Light was built in 1825 to guide vessels partaking in the area's growing lime trade. After receiving approval from President John Quincy Adams, a thirty-foot tower was built atop a soaring promontory. In its early years the Owl's Head Light was decrepit. Seven years after its completion, repairs were already being made and a I.W.P Lewis inspection report from 1843 noted that the entire complex was "in a filthy state" and in desperate need of attention. A round brick tower was finally built in 1852 and a new keeper's house followed soon after in 1854. Two years later, in 1856, the current fourth-order Fresnel lens was installed, replacing the original lens.

This information has been shared with the Lane Project by Jeremy D'Entremont. More information can be found at his website, www.newenglandlighthouses.net or The Lighthouse Handbook New England.

Letter

Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, Mass.

Thanks for "View of Owl's Head", a moonlight scene: "Mr. Lane, Dear Sir, when I expressed to you, during your visit to us, the last summer, my admiration of moonlight scenes, I did not for a moment suppose that I should ever become the possessor of one, and that so beautiful as "The View of Owls Head," which you have so kindly, and in so delicate a manner presented to me, and for which, I now beg you to accept my heartfelt thanks, also, be assured, if your pleasure in giving has been half equal to mine in receiving, you have been amply repaid for your kindness, and I alone, am the debtor. . . ."

Commentary

Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine is probably Lane's best-known work. He greatly simplified a popular artistic motif—the idyllic harbor view—in virtually every detail. The viewer looks out onto a contemporary coastal town with its commercial traffic, but sees few props in the foreground and background that would preoccupy one with thoughts of daily affairs. Instead there is a single boatman gazing at a seemingly unpopulated bay. Lane recorded the distinctive profile of Owl's Head with its tiny lighthouse clearly silhouetted against the evening sky.

Geometric clarity and simplicity set Lane's work apart from landscape scenes of the previous century. In Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine nature is a presence that envelops and transfixes the solitary boatman, but the picture that presents this vision retains the modest format and a bit of the decorative appeal of an earlier era.

– Text has been adapted from Theodore Stebbins, Carol Troyen, and Trevor J. Fairbrother, A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting, 1760–1910 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1983).

[+] See More