loading

Fitz Henry Lane

HISTORICAL ARCHIVE • CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ • EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE

An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

Catalog entry

inv. 203

Boston Harbor

1856 Oil on canvas 25 1/2 x 42 1/2 in. (64.8 x 108 cm) Dated verso: 1856

|

Related Work in the Catalog

Supplementary Images

Provenance (Information known to date; research ongoing.)

William H. Hill, Royalston, Mass.

Donald M. Hill, Royalston, Mass.

Calvin Hill, Boston

Vose Galleries, Boston, 1977

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Tex., 1977

Exhibition History

Rhode Island Society for Domestic Industry, Rhode Island, September 3, 1867., no. 70, Boston Harbor.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, American Paintings from Copley to Ryder, November 17, 1988–January 29, 1989.

Traveled to: Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 23–4, 1989.

Traveled to: Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 23–4, 1989.

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gems from the Collection, June 7–August 17, 1997.

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, New Harmonies: Masterpieces Across the Collection, May 30–August 16, 1998.

Published References

Amon Carter Museum: An Introduction. Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1982., pg. 34.

Ayres, Linda, et al. American Paintings from the Amon Carter Museum. Birmingham, AL: Oxmoor House, 1986.

Gaehtgens, Thomas W. Bilder aus der Neuen Welt: Amerikanische Malerei des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Prestel, 1988.

Wilmerding, John. Paintings by Fitz Hugh Lane. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1988., ill. in b/w p. 56 fig. 5, Boston Harbor.

American Art, American Vision: Paintings from a Century of Collecting. Lynchburg, VA: Maier Museum of Art, Randolph-Macon Woman's College, 1990.

Cash, Sarah. American Art: Paintings from the Amon Carter Museum. Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1992., p. 20.

Kammon, Michael. Meadows of Memory: Images of Time and Tradition in American Art and Culture. Austin, TX: University of Texas, 1992., ill., p. 99, text p. 98.

Roters, Eberhard. Malerei des 19. Jahrhunderts. Cologne, Germany: DuMont, 1998.

Junker, Patricia. An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. New York: Hudson Hill Press; in association with the Amon Carter Museum, 2001., p. 60.

Lawton, Rebecca. "Amon Carter Museum." American Art Review 13, no. 6 (November 2001).

Lawton, Rebecca. An American Album: Highlights from the Collection of the Amon Carter Museum. Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 2005.

Commentary

The setting for this busy scene is based on a drawing by Lane of Boston as viewed from Governor’s Island and apparently updated in 1853-54 Boston Harbor, 1850s (inv. 158). The steeple of the First Baptist Church (completed in 1853) appears near the foremast of the approaching coastal steamer, confirming a post-1853 date for this painting. It is close to noon, with sunlight passing through breaks in an overcast sky to illuminate the steamer and ships’ sails in the middle ground, while vessels in the foreground float darkened and becalmed.

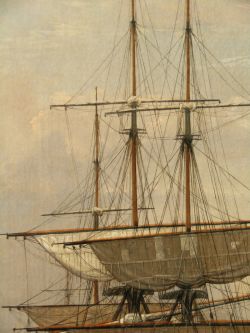

The array of vessel types is what one would expect to see in mid-19th century Boston. The two large ships are merchantmen; at left a packet ship (1) in the transatlantic trade, distinguished by her false painted gunports, is being assisted by a harbor tug (10) as she leaves port. At right is a clipper ship (2) at anchor, her sails “hanging in the gear” to dry from an earlier rain shower. Behind her is another, smaller, three-master – probably a bark (3) used in long-haul coastal trade or deep-water voyages where speed was not critical.

Astern of the packet ship is a half-brig, or hermaphrodite brig (4), a very handy rig for coastal shipping – here or abroad. When in the latter situation, she would return to home port after spending most of a year trading between overseas ports, most commonly in northern Europe and the Mediterranean. On the other side of the packet ship is a topsail schooner (5) used in the American coastal trade for longer offshore passages, where the square sail helped greatly to steady the vessel’s motion in ocean swells. At far left is a small coasting schooner (6) – a relic from the early 19th century, but still sound and useful for short voyages to supply small coastal communities.

In center foreground is a packet sloop (7) used to carry passengers and goods to small coastal communities around Massachusetts Bay. They sailed on regular schedules to specific ports, were smartly handled, and well-maintained. In left middle foreground is a large, burdensome rowing boat (8) which is probably being used for “lightering” – landing cargo from an anchored vessel when space for wharf-side unloading was unavailable.

Outbound for some distant New England port unreachable by rail is a coastal packet steamer (9) with passengers and high-value goods (bulky, low-value cargos were left to sailing vessels). The services of this vessel type were vital along the Maine coast, whose bays, capes, and islands were too expensive, if not impossible, to service by rail. Smaller versions of this steamship type served coastal communities closer to Boston with speed and comfort (except during bad weather) not offered by stage coaches.

The harbor tug (10) escorting the packet ship is of the “steam propeller” type, and an uncommon sight in Lane’s Boston views. Unlike New York, Boston Harbor was more compact with less need for tugs. Many large vessels were moved from one pier to another by “warping” – hauling the vessels from pier-head to pier-head using wharf capstans and tow lines. A tug fleet for harbor work was slow to develop until after the Civil War.

The small schooner at far right is the least typical of a Boston working vessel, and its inclusion may be whimsy on Lane’s part. It is a pinky (11), so-named for her “pink” stern (from the Dutch word for “pinch”), which ended in an upswept and pinched extension of her bulwarks. Pinkies evolved from Chebacco boats, named for the community of their origin (now called Essex) and had a major role in the revival of Cape Ann’s fisheries in the last decade of the eighteenth century and the first two of the nineteenth. Many pinkies survived into the mid-19th century, and it is possible that they appeared at times in Boston.

–Erik Ronnberg