An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM

The Drawings

The exercise of drawing outdoors provides the artist with opportunities for truthful recording and any manner of interpretation and expression. Drawing in the open air combines the charm of being immersed in nature with the allure of capturing the freshness and spontaneity of a subject. Drawing “en plein air” can offer a rewarding physical challenge and the promise of adventure. All of this holds timeless romantic appeal. Yet drawing outdoors, “roughing it” and contending with the natural elements while encumbered with equipment and materials, can also test an artist’s fortitude, especially one with impaired mobility. Nuisances like heat, bugs, and above all, wind, can foil the artist’s enjoyment, not to mention productivity and quality of work. Limiting factors such as daylight and inclement weather can make the ability to work quickly and without concern for refinement a necessity.

In Folly Cove, Lanesville - Gloucester, 1864 (inv. 157) an intimate inscription (lower left) and depiction of a boat sailing away lend poignancy

to this classic view that Lane made the year before he died.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1927 (485.102)

After returning to Gloucester from Boston in 1848 and until 1864, Fitz Henry Lane produced over one hundred and forty preparatory sketches from nature. Landscapes of marine and inland views make up the vast majority of these, but the tally includes minor studies as well as unfinished sketches applied to the backs of twenty sheets. Drawings that have been accounted for include those in the collections of the Cape Ann Museum, the Farnsworth Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, the Harvard University Art Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

An appreciation for the drawings as a body of work worthy of independent study must still acknowledge that, first and foremost, the drawings were tools for Lane the painter. (1) As such, the drawings were descriptive documents intended to record, in varying degrees of detail, the appearance of the subject and ultimately provide the artist with references for his oils painted in the studio. (2)

The manner in which the drawings are liberally annotated emphasizes their significance as permanent records as well as working documents. Sometimes as many as four separate inscriptions are found on the drawings. Most of the inscriptions are ascribed to Lane’s close friend, Joseph L. Stevens Jr., and are thought to have been added shortly after Lane’s death. Altogether, these notations reflect a concerted effort to record first, the artist, followed by date and place or view. Additional tangible details include the names of other parties present during the outing, and the recipient of the oil painting for which the sketch was made. Less often, in distinctive block letters, Lane signed the drawings using Lane del., F.H. Lane del., and F.H. Lane. In this same block print Lane occasionally added the date or named the view.

A technical examination of Lane’s drawings was undertaken without the benefit of any first- or secondhand accounts to augment direct observation of the sheets themselves. The complete absence of any diary entries, letters, or other writings concerning, for example, the choice and procurement of art supplies, the artist’s personal musings about the activity of drawing from nature, or any insight into specific outings or sketches, is unfortunate for such an investigation. Nevertheless, by careful study of their material aspects—namely, graphite pencil and paper—questions as to what, and how, can be answered by the drawings themselves. A close inspection of the graphite and styles of mark-making reveals much about Lane’s choice of drawing tool, and his drawing technique. Questions about the types of paper Lane preferred to draw on and how he used the sheets—often to make multiple sheet compositions—are also answered. The process of gathering and analyzing the empirical data, coupled with reviewing the literature—including contemporary artists’ drawing manuals and artists’ material catalogues —enables one to arrive at firm conclusions and well-informed theories about Lane’s materials and methods for drawing from nature.

Even taking into account a relatively short season for outdoor work, Lane’s drawing oeuvre is rather small. Speculation about this modest number of working drawings also takes into account the dearth of earlier sheets (pre-1848), studio work, and ship studies. Are there still caches of Lane drawings out there still to be discovered? Were some of Lane’s drawings lost or destroyed? Regardless of how productive Lane may have been, there is no question that drawing from nature was a serious pursuit for him. It was the starting point for his creative endeavors and vital to his success as a marine and landscape painter.

So, imagine a clear summer morning accompanied by a gentle off-shore breeze, and a secluded spot to take in a glorious view filled with possibilities. On such a day, armed with graphite pencils and loose sheets of paper, Lane would set out to explore and record his environment and gather the raw material for his paintings. He often traveled by boat, and on numerous occasions drew while on the water. “Drawn from a boat,” “sloop,” or “steamer,” is written on at least eleven of the drawings. For other views, Lane’s vantage point and placement on a boat has been proposed by Erik Ronnberg, a long-time Cape Ann native, Lane scholar, and marine historian. (See list below). Lane also went inland to capture the countryside in and around Gloucester, but his coastal views—principally of Gloucester and of Maine’s Penobscot Bay and Mount Desert Island—occupied the majority of his efforts. From these unobstructed horizontal vistas, Lane would choose the settings for his highly finished oils, sometimes compressing space or subtly modifying the view in other ways for compositional refinements and pictorial effects. (3)

With a few exceptions, Lane’s plein air sheets were drawn with graphite pencil and can be divided into two categories. There are the studies of solitary objects, such as a rock or tree, or a simple watercraft, such as a sloop. These drawings were executed to varying degrees of finish on single sheets of paper. This group seems to be missing sketches of vessels, in particular the impressive three-masted ships that are so prevalent in Lane’s harbor-view paintings. Lane was extremely practiced at drawing these more complicated vessels, demonstrated by his ability to skillfully and accurately portray them in every variety of activity and from many vantage points in his paintings.

View in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 143)

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1927 (485.67)

This three sheet composition features many of the elements typical of Lane’s views. At the same time it is uncharacteristic: it is one of only a few drawings that was squared (possibly for transfer), and, even more exceptional, has perspective lines receding to a vanishing point; these additional notations lend interest to its function as a working drawing for an oil painting.

More numerous and significant in this corpus of work are Lane’s views: the panoramic sketches that provided the backdrops for his oil paintings. Often drawn on multiple lap-joined sheets to extend the composition horizontally in one or both directions, these drawings feature the scenery that characterized Lane’s environment: rural landscapes with distant towns, expansive and varied shorelines (and coastlines), unpopulated harbors, and isolated rocky beaches. While many drawings include a tentatively drawn boat—perhaps for scale reference—more conspicuous is the absence of the numerous types of sailing vessels that feature prominently and, in the case of some harbor-views, crowd Lane’s paintings.

In the paintings, watercraft are vital pictorial elements: they punctuate the vista and lead the eye through the composition, they reinforce the receding plane from foreground to horizon, their sails provide lively patterns of light and dark, and their masts are vertical accents that counter the persistent horizon. The vessels also tell stories, as Lane was a master ship portraitist. His ability to accurately portray a vessel with all its specificity of structural detail and sailing activity was essential for Lane’s contemporaries—a far more nautically informed audience—and this ability continues to inspire wonder in viewers today.

The drawings often include buildings, but human figures are notably absent, and the vast spaces defining sky and water remain unarticulated so that weather conditions and time of day are unspecified—all of these elements were recreated or invented later, in oil, and in the studio.

As is often the case with nature sketches—made by both the professional and amateur—many of Lane’s drawings, or at least aspects of them, are sensibly rather than beautifully executed. To a great extent, Lane’s field sketches are cursorily drawn, with a strong reliance on outline and repetitive marks culled from a repertoire of shorthand that has both formulaic and individualistic features. The drawings are fundamentally unlike his meticulously rendered lithographs and oils. In these unpolished, even unfinished sheets, Lane defined the relationships of the landmasses, the distances between them, and their relative proportions. He captured the essentials of the indigenous scenery and contours of the landmarks which provided further specificity: coastlines, frequently composed of rocky banks and outcroppings; plant life, loosely described with silhouettes or repetitive marks to create patterns and textures; simply outlined buildings.

Flora and Rocks:

Vegetation and rocks are two pervasive elements in Lane’s landscapes. The prevalence of cursorily drawn foliage suggests that Lane simply wanted to record enough information about the plant growth to make reasonably accurate depictions later. Foliage is a transient element that can be fussy and time-consuming to draw and which lends itself to formulaic representation, as seen in Lane’s lithographs and paintings. The immediate foregrounds of Norman's Woe, 1861 (inv. 114), and View in West Parish on Lower Road, c.1863 (inv. 124), are good examples of hastily drawn foliage. An exception to this tendency is seen in Blue Hill, Maine, 1851 (inv. 244), where the foliage throughout the composition has a relatively high degree of finish and specificity that suggests a relaxed pace, more careful observation, and perhaps more than one sitting.

In Castine from Fort Preble, 1851 (inv. 169), Lane used a robust outline and greater care and specificity to accentuate

a variety of leaf types in the foreground passage of foliage.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1927 (485.26)

Practical or not, this handling provides insight into the artist’s attitude and priorities and underscores the intimate nature of the sketches: they were personal recordings and references not meant for public scrutiny. When sketching on paper, Lane did not have to follow the strict regime of drawing with crayon on stone, nor was he concerned with a polished product to sell. He could use shortcuts and make marks that were hurried and unrefined because it simply did not matter—the drawings were merely a means to an end. From this perspective, one sees a greater freedom in the drawings and the artist’s graphic style is bared to a greater extent.

Rocks—prolific in Lane’s views—were often hastily drawn but, perhaps more than any other topographical feature, held Lane’s attention. He articulated their three-dimensional shapes in simple planes using outline and tone and sometimes with extensive shading that demonstrates a concentrated study of form and light. Rocks, cobbles, and boulders possess structural and tactile qualities that are pleasing to draw—at least we can infer this from Lane’s handling of them in many of his compositions. Moreover, rocks were part of the architecture of the landscapes and required more accurate recording for later use in a painting.

For describing rocks, as well as other permanent features like the distant landmasses and even more remote horizon line, Lane often stitched the contours together with many small lines or used lines gone over repeatedly in a scratchy manner. But ultimately there was no fixed approach, and Lane’s rocks display an array of line qualities: firm and confident, fluid and meandering, repetitive and sketchy, and hesitant and interrupted.

Gloucester Beach from the Cut, 1850s (inv. 103)

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1927 (485.89)

In this composition, the rocks along the foreground beach build in degree of finish from left to right: from cursorily drawn to fully realized. Lane’s more descriptive line and attention to shading to create three-dimensional forms reveal his pleasure and skill in drawing these ubiquitous geological features.

Buildings:

Although Lane’s views lack human activity, he included evidence of human habitation, and incorporated houses, churches, and commercial buildings. These structures were drawn predominantly with short, abrupt, and often firmly applied lines that clearly delineate and enhance the buildings’ rectilinear aspects. Strong similarities are seen in Lane’s drawing vocabulary when comparing the buildings in his drawings to those in his lithographs. At first glance, the lines are so exact that they seem to have been drawn with the aid of a straight-edge.

These three drawings Castine from Hospital Island, 1855 (inv. 166), Gloucester from the Outer Harbor, 1852 (inv. 72), and A Rough Sea, 1854 (inv. 12), depict well-developed towns with architectural structures that are drawn with a degree of precision and specificity such as to indicate map-like accuracy. Accuracy and precision do not automatically connote mechanical means however, and with close looking the rectilinear lines are observed to have variations that belie the use of a straight edge.

Gloucester from Steepbank, c.1855 (inv. 125)

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., 2013 (2013.19.7)

In Gloucester from Steepbank, erasing and corrections to the buildings are clearly visible. Variation in line quality, from pale and relaxed to dark and emphatic, demonstrates Lane’s use of atmospheric perspective to enhance the illusion of distance. In this same sketch, the foreground and middle ground were knocked out in a hurried manner, but the more distant town with several church steeples and densely built houses was drawn with an exactitude that conveys truthful recording. This drawing is spattered with tideline stains that bring to mind water droplets from a rain shower. These same stains can be found on several other sheets but should not be confused with the more prevalent fox stains that now mar many of the sheets. Fox stains or foxing refers to a variety of orange to brown blotchy stains that point to (prior) mold activity often due to damp storage conditions.

Lane’s practical approach to landscape drawing can also be seen in his monochromatic sketches: drawings made with a uniform value, hue, and unvaried mark, and with minimal information. His monochromatic technique is well illustrated in View in Town Parish, 1863 (inv. 126), Boston Harbor, 1850s (inv. 158), and Sketch from Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1863 (inv. 145). The Gloucester Harbor sketch also looks unfinished and was probably done from a boat. In Boston Harbor, 1850s (inv. 158), drawn from a great distance with a sparse and faint graphite line, the miniscule dome of the Massachusetts State House on Beacon Hill barely identifies the locale, yet this single, bare-bones sketch may have served as the backdrop for many of Lane’s Boston Harbor paintings.

Working methods:

To create his multi-sheet panoramic views (that can be as wide as 52"), Lane must have worked on a larger surface, possibly a drawing board or lap easel. Multiple pinholes consistently found in the corners of individual sheets indicate he secured his overlapped sheets by pinning so it is reasonable to infer that his drawing board had a pin-able surface. Contemporary artists’ materials catalogues from Boston suppliers advertise drawing boards made from mahogany and deal (wood from fir or pine trees used for making furniture). Either wood could have provided a suitable surface for pinning. Close observation of the drawings revealed many instances of equidistant spacing between two pinholes; therefore it was gratifying to discover double-headed pins advertised in the 1860 artist’s materials catalogue Wheeler and Whitney’s of Boston. A double-headed pin explains this equal spacing and would have held the sheets in place much more effectively than a single pin. Xs were clearly drawn (one at the top and one at the bottom) to bridge the lap-joined sheets, and there is often a continuous vertical graphite line abutting the edge of the overlapping sheet. Several of the multiple sheet supports have matching tick marks: ‘ , ‘’ , or ‘’’ on the upper adjacent corners of two overlapped sheets. Presumably all of these marks were made by Lane to insure proper registration later in the studio, where he may have glued the sheets together. (4) Unevenly cut edges suggest that Lane trimmed his papers hastily in the field as he needed to crop/adjust the format and add paper to build his multi-sheet supports. Horizontal edge-trimming along the top and/or bottom edge is customary, but vertical trimming is also common.

It is evident that Lane kept the task of drawing outdoors uncomplicated. Other than a few essential drawing materials, perhaps he had some items for comfort, such as a chair and picnic lunch, that could have been carried by one of his travel companions.

The Pencil:

By Lane’s day, the very portable, ubiquitous and seemingly simple modern graphite pencil was already a highly engineered, remarkably versatile, and sophisticated instrument. Most often encased in wood, this pencil used fabricated leads that came in a range of hardness that correlated with clay content and the strength of the mark: harder leads containing more clay made a paler greyer mark and softer leads with less clay, a darker and blacker mark. Contemporary drawing manuals recommended the modern graphite pencil as one of the preferred drawing tools and provided explicit instruction (although not always the same instruction) on every aspect of pencil drawing. (5) In the nineteenth century and especially between the years 1800-1860, American artists in particular embraced the graphite pencil as their fundamental drawing tool; they found its versatility, ease of handling, and portability ideally suited for nature sketching. (6) Line was the essence of form and the foundation of drawing. Lessons on landscape drawing focused on the linear aspects of drawing and advised students to begin by establishing the shape of the subject with outline. (7) The erasable (8) graphite pencil was perfectly suited to draw a line in all its variety of expression: mechanical, spontaneous, lyrical, emphatic, meandering, hesitant, flowing, broken, controlled and calligraphic. For Lane, the pencil line was an indispensable means of representation.

Some drawing manuals expressly instructed artists to vary intensity and tone by changing pencil grades and to “always use the lightest pencil that will produce the desired effect without indenting the paper.” One manual included the following instructions:

1st. Let the pupil be provided with four pencils, of different grades, to distinguish which some drawing-pencils are marked with letters, others with figures. No. 1 is very soft and black, used only for the darkest shades; this pencil corresponds to B.B. of those marked with letters. No. 2, less soft and black, is the pencil most used for bright, spirited touches and shadings; it is of the same grade as B. No. 3 is hard, used for outlining etc., and is the same as H. No. 4 and H. H. are very hard, for fine lines and delicate shades. (9)

Indeed, some artists exploited the tonal range of the modern graphite pencil so that within a single drawing the distinction between grades, i.e., a harder grey lead and a softer black lead, is obvious. However, within a single pencil lead, or “grade” of graphite, a range of value can be obtained by varying pressure of application. Therefore, between adjacent grades, and even among grades in close proximity, a great deal of overlap can be achieved. Hence, even in drawings that show appreciable tonal range, typically it is the inability to distinguish different graphite grades that must be presumed.

By comparing Lane’s graphite marks to marks made with today’s poly-grade drawing pencils, it is estimated that Lane primarily worked with middle-range leads and only occasionally with significantly harder or softer leads. In a single drawing, Lane probably did not intentionally alternate pencil grades, relying instead on adjusting pressure of application to achieve tonal range; for example, applying more pressure to emphasize the rocky foreground terrain, and less pressure to articulate the distant island and horizon line. This economy of means seems entirely in keeping with Lane’s practical approach to outdoor sketching. While Lane may not have exploited the poly-grade graphite pencil fully, his affinity for the tool is unsurprising given his experience as a lithographer working in the crayon manner tradition with various grades of lithographic pencils. (10)

Fresh Water Cove, Gloucester, c.1864 (inv. 112). Detail of graphite stroke with characteristic metallic luster and slight indentation of the sheet. In this investigation, it was rare to find a more vigorously applied dark mark where the paper was actually indented from the pressure. In Fresh Water Cove, Gloucester, Lane frequently used a robust application of graphite to create this more finished sheet.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1927 (485.93)

Photo © Moyna Stanton

According to design and function, drawing with a wood-cased pencil entails re-pointing, that is, cutting away the surrounding wood and further sharpening the graphite core with a knife or sandpaper to achieve a good point. A pencil point wears down fairly quickly and is immediately composed of many tiny facets that are constantly changing, so very few lines are made with an actual point, but rather blunted facets on the point. If leads became too worn, Lane could have simply sharpened the pencils or switched out dulled pencils for fresh. For shading and more tonal interpretations, Lane placed individual lines close together, sometimes so delicately with a blunted point that the lines merge seamlessly. Only very occasionally did he use stumping to blend the graphite for soft tonal effects, a technique best seen in his more finished rendering Beached Hull, 1862 (inv. 191). Lane relied heavily on the common return-stroke and also used a host of other notations, including scribbling, to lay in color and texture.

With close examination it is occasionally possible to find lines that appear scratchy due to sharp indentations in the paper and gaps that interrupt the uniform graphite stroke. These marks, familiar to anyone who has used a wood-cased pencil, indicate a hard impurity in the graphite or interference from the wood sheath as the graphite point wears down and is interrupted by a high spot of sharpened wood.

A close-up of this boulder in Norman's Woe, 1861 (inv. 114) shows numerous scratchy marks

made by a high point on the pencil's wood case or a hard impurity in the graphite.

The Paper:

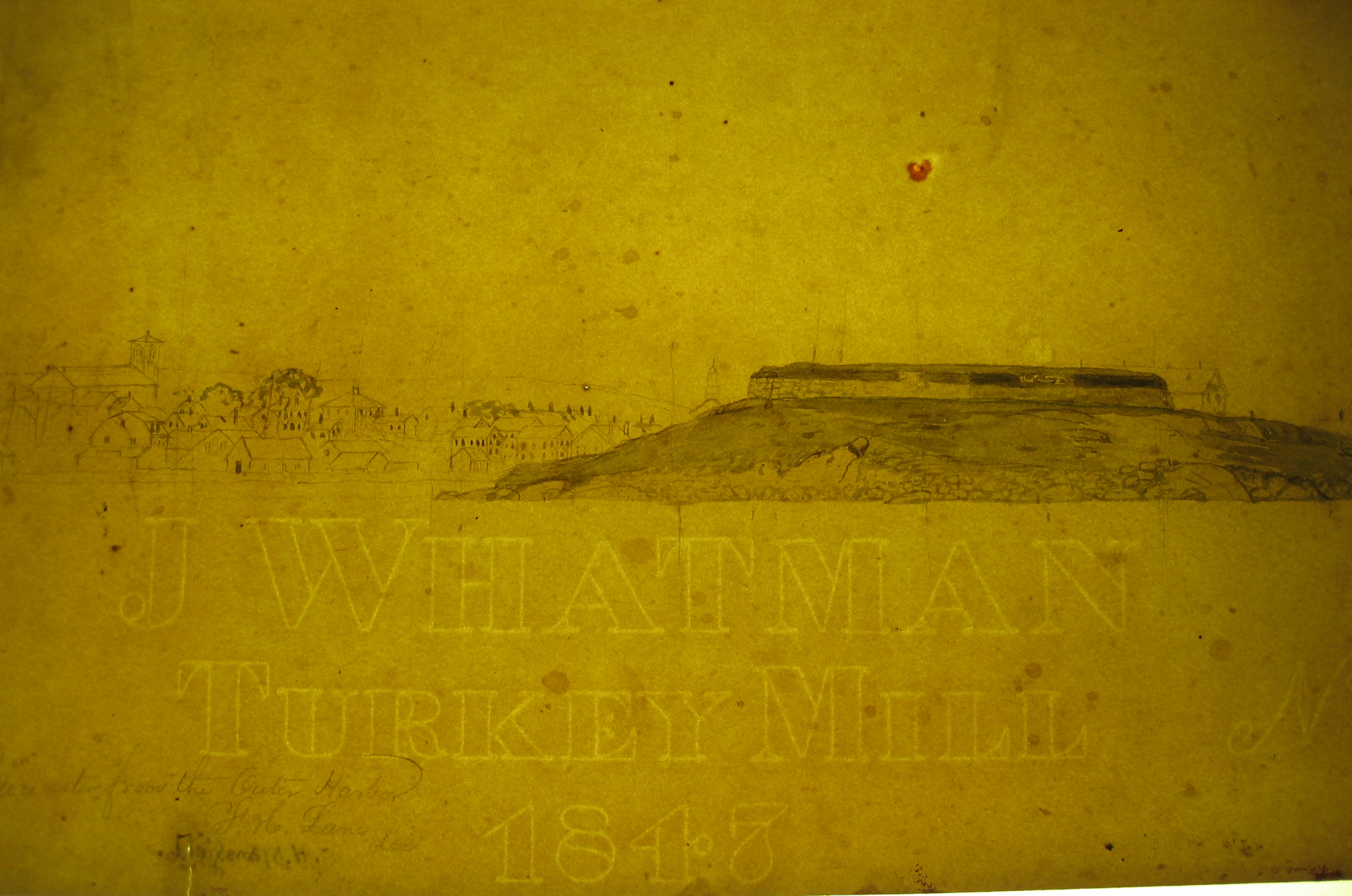

Final appearance of a pencil mark is also determined by certain qualities of the drawing support—typically a simple sheet of paper—of which there are myriad varieties. In making his field sketches, Lane used individual sheets of good- to high-quality, wove, drawing papers. The absence of original edges and inability to examine all the sheets fully bars conclusion, but there is no evidence that any sheets were originally bound in any type of sketchbook. However, regardless of their original format, Lane used them as individual sheets. (In previous articles on Lane’s drawings, scholars may have assumed that Lane used a sketchbook because it was a traditional material for outdoor sketching). Lane’s papers range from pale beige to off-white in color, and can be further characterized as medium weight and with surface textures ranging from smooth with a slight tooth, to more textured, to slightly rugged. (11) Whatman paper watermarks, typically a partial Whatman / Turkey Mill and date, (1847; 1849), found in several of the brighter off-white and softly textured sheets, identify this very fine, English-made artists’ paper as one of Lane’s preferred drawing supports. That Lane often chose the highest-quality and most expensive variety of paper available for his working drawings merits mention, but defies a tidy explanation. An attempt to economize with this costly supply is perhaps seen in his use of both sides of the support, (approximately 16% of the sheets were drawn on both sides) and by occasionally drawing a second partial composition above the first. Whatman papers with slight flaws called "retree" (spelled "retrieve" in N.D. Cotton’s Artists’ Trade Catalogue from 1832) were also available at a reduced price.

Gloucester from the Outer Harbor, 1852 (inv. 72) detail showing Whatman Turkey Mill 1847 watermark taken with transmitted light.

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., Gift of Samuel H. Mansfield, 1927 (485.103)

Photo © Moyna Stanton

While not readily distinguishable in these drawings, it is estimated that both hand-made and machine-made papers are represented. (12) Sometime between 1838 and 1846, the first Fourdrinier papermaking machine was installed at the Whatman Turkey Mill, and until 1859, when Turkey Mill ceased hand production, this very important English mill produced both hand and machine-made, high-quality, white wove papers. (13) Therefore, even in these watermarked sheets, where the maker, mill, and date of manufacture are identified, the method of fabrication, handmade versus machine-made, remains uncertain.

Pencil quality, grade (i.e., hardness), and artist’s handling (i.e., amount of pressure), all contribute to the appearance of the pencil line and final drawing. Paper properties such as color, and in particular, surface texture and tooth also significantly influence the visual qualities of the graphite line—its value/color, texture, and uniformity—and final outcome of a drawing. As a graphite pencil moves across a sheet of paper, the abrasive character of the sheet’s surface texture causes particles of graphite to be deposited. On a paper with a relatively uneven, rugged surface, the pencil will tend to hit the high points harder and skim more gently over the low points—at times entirely missing some cavities, yielding a pencil line that is more broken up with white paper, and soft-edged. This interaction amplifies the pencil’s soft crumbly quality as well as the paper texture. A more textured paper will tend to enhance the impression of an interrupted and hesitant line and a smoother paper will encourage a uniform, fluid, and confident line.

An appreciation of Lane’s drawings is enhanced by a more intimate understanding of the features and working properties of graphite pencil and wove paper. Yet it remains extremely difficult to make generalizations or identify trends in his field sketches: whether working on a paper with a smooth, toothy, or slightly rugged surface texture, Lane achieved a range of drawing qualities.

In conclusion, even within this relatively homogenous body of work, made with seemingly simple, unvarying, and commonplace drawing materials, Lane’s approach varied considerably. A grasp of Lane’s flexibility, of the subtle complexities of his drawing materials, and the nuanced manner in which they interact, are all important considerations when attempting to characterize Lane’s drawing style, including the attempt to identify a mechanical versus free hand behind his marks.

Examples

Rocks:

1) Fresh Water Cove, Gloucester, c.1864 (inv. 112) (CLOSE-UP foreground, left side) Although Fresh Water Cove is depicted in the distant right, this drawing features a farm with a prominent meandering rock wall. For much of the wall, Lane painstakingly outlined the individual rocks in a bold graphite line, but with a lack of specificity consistent with distant observation. Then in the foreground left, he used line and shading to articulate detailed surface features and to represent particular rocks and their relationship to each other.

2) Near Southeast View of Bear Island, 1855 (inv. 135) From a fairly distant vantage point Lane described the entire rocky coastline of the island. In this topography, he used fairly robust graphite marks to create a lively rhythm of highlights and shadows and textures and patterns that holds the viewers’ interest, as well as faithfully documents the highly variable boundary that, with its sheer cliffs, protrusions, overhangs, and eroded undercuts, appears to offer no safe place to put ashore.

3) West Harbor and Entrance to Somes Sound, 1852 (inv. 179) In this sketch Lane does not make a strong statement with the foreground or distant shore lines. The foreground rocks, in particular, are quite unremarkable, essentially glossed over in Lane’s adept shorthand, which lends an unfinished and uncertain quality to the favored element.

4) Looking Westerly from Eastern Side of Somes Sound near the Entrance, 1855 (inv. 180) Lane’s confident contour line and unlabored approach is nicely captured in this rocky shore. Rounded boulders comfortably intermingle with more jagged ones to capture a particular terrain. In one shaded rock face, three tiers of return strokes are clearly evident.

5) View at Bass Rocks Looking Eastward, 1850s (inv. 156) Lane’s adept use of graphite for realistic depiction is clearly conveyed across these three sheets of joined paper. He defined the rocky coast as it spills out from the picture plane with topographical precision, while still taking advantage of the opportunity to render a picturesque representation with a fluid and subjective line that entices the viewer to explore and scramble over the rocks on foot.

6) South East View of Owl's Head , from the Point of the Island, 1855 (inv. 129) The extreme foreground rocks drawn in an abbreviated manner with almost pure outline allow the more distant rocky island coast, drawn with more attention to light and shadow, to become the focus in this drawing, as the title suggests. In this work, the fluid, uninterrupted line quality also clearly conveys the paper’s smooth texture.

7) South East View of Owl's Head, from the Island, 1855 (inv. 130) (foreground rocks) Sharp directional lines capture this craggy terrain of boulders. Unsmoothed by weathering, these rocks seem to retain the powerful directional force of the glaciers that moved them some eight thousand years earlier.

8) Beach and Neck of Land, c.1864 (inv. 160) Sketched on a more textured paper in a loose manner that conveys a swift and casual approach, these close foreground rocks do not dominate the view, but intermingle with the tall beach grass in a balanced manner.

Materials/technique:

9) Chebacco River, etc., from West Parish of Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 155) is an example of a drawing possibly made with a harder and paler graphite pencil. For such a deeply receding view, there is very little variation in darkness of mark or level of detail to convey atmospheric perspective. A subtle focal point is created in the middle ground, on the right side of the sheet, by intentionally smearing the graphite and applying some slightly bolder marks. Nevertheless, a pale silvery color pervades the entire drawing.

In this detail of Coffins Beach from the Loaf, 1862 (inv. 153) it is possible to see where many of the side-to-side graphite lines

have picked up the ribbed texture of the underlying support.

Shorthand technique:

10) Norman's Woe, 1861 (inv. 114) The rudimentary back-and-forth return stroke is a staple in the draftsman’s repertoire, especially for sketching. Lane employed it extensively in this sheet in a casual and variable manner that conveys facility and swiftness.

11) Bear Island from the South, 1855 (inv. 134) Repetitious, closely spaced vertical lines (possibly made with a tight return stroke), used to articulate the sheer rocks along the shore, yield to softer looping forms to show the transition to low-growing vegetation on the steep hill. Sharper vertical marks, some with horizontal accents, denote taller growth to the left and right.

12) Mount Desert Mountains, from Bar Island, Somes Sound, 1850 (inv. 181) Lane captured the great variety of plant life in this foreground expanse by varying scale and concentration of his marks as well as by clearly separating distinct plant morphologies with the repetition of specific notations.

13) From West Manchester Shore, 1850s (inv. 162) For this foreground vegetation, Lane virtually scribbled, evoking haste and rejection of detail, yet capturing the essence of the scruffy, tenacious beach grass on a sand dune.

Paper texture:

14) Ten Pound Island in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 105) West Harbor and Entrance to Somes Sound, 1852 (inv. 179) In these single-sheet compositions, the paper texture is readily apparent in the foreground and distant elements. In the textured sheet, the line is finely disrupted, with exposed paper lending a soft quality to even the most brusquely drawn lines. In contrast, the smooth paper yields a line that appears solidly colored, smooth, and fluid.

15) Rocks, 1850s (inv. 115) Rock Study, c.1856 (inv. 116) It is important to remember that in all of these examples, "smooth" and "textured" are relative terms; taken as single works, the paper texture of either would not necessarily stand out as a prominent aspect of the drawing. Rocks, executed on a relatively textured paper, considered next to Rock Study, drawn on a relatively smooth sheet, nicely illustrates the impact that paper texture can have on the overall appearance of the drawing.

16) Gloucester Outer Harbor from Eastern Point, 1850s (inv. 148) Westward View from near East End of Railroad Bridge, Mid 1850s (inv. 118) In the first example, the more textured sheet enhances the interrupted hesitant quality, whereas Westward View, a very similar, albeit more finished composition on a smooth paper, has a completely different feel, with lines that appear fluid and firmly applied.

17) View at Bass Rocks Looking Eastward, 1850s (inv. 156) View from Rocky Neck, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 137) Different paper textures do yield unique qualities in these two sketches, yet, in terms of the artist’s overall approach, as well as his specific drawing technique for capturing the views, they also have much in common. Both show a heavy reliance on outline to capture with topographical accuracy a field of rocks in the foreground and, in both the jutting and isolated land masses seen across a moderate expanse of water, are handled in the same manner: more abbreviated, yet completely described to both sides of the sheet.

18) View from Stage Rocks, Gloucester, 1850s (inv. 108) View from Rocky Neck in Gloucester Harbor, 1850s (inv. 99) These two depictions of large and random rock deposits are of similar scale and vantage-point and alike in their balanced use of outline, tone and description of vegetation sparsely interspersed in the rocks.

19) Town Parish, 1863 (inv. 127) View in West Parish on Lower Road, c.1863 (inv. 124) Drawn from very different vantage-points, these two drawings of inland views present a dramatic contrast and perhaps a reversal of what one might expect. In Town Parish, drawn on a smoother paper, there is a quiet, understated quality that conveys restraint. Next to this sheet, View in West Parish, on relatively textured paper, has a brusque line quality and overall bolder approach that expresses confidence.

List of views drawn from a vessel afloat:

Stage Rocks and Western Shore of Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1857 (inv. 106) “sketched from a lumber loader vessel.”

Owl's Head from the South, 1851 (inv. 131) “Taken from a Steamer’s deck while passing”

North View of Owl's Head, 1855 (inv. 132) “…Taken from our boat in the early afternoon of a beautiful day…”

Northeast View of Owl's Head, 1851 (inv. 133) “Taken from Steamers deck(s) in passing.”

Camden Mountains from the South Entrance to Harbor, 1855 (inv. 171) “Sketch taken from the boat on our…”

Camden Mountains from the Graves, 1855 (inv. 172) “sketch made on our second day’s cruise while going from Rockland to Camden”

Camden Mountains from the Penobscot Bay, 1851 (inv. 175) “Taken from Steamer’s decks in passing.”

North Westerly View of Mount Desert Rock, 1852 (inv. 176) “Taken from decks of Sloop Superior at anchor.”

Somes Sound, Looking Southerly, 1850 (inv. 178) “Lane made this sketch sitting in the stern of the boat General Gates as we slowly sailed up the sound at Mt. Desert on a lovely afternoon of our first excursion there.”

North East Harbor, Mount Desert, 1850 (inv. 183) “Taken from Boat Admiral Gates at anchor.”

Southwest Harbor, Mount Desert, 1852 (inv. 184) “Taken from Sloop Superior at anchor.”

Views probably from a vessel afloat (not annotated as such, but proposed by Erik Ronnberg):

South View of Owl's Head, from the S. End of the Island, 1855 (inv. 128) (Inscriptions lower right are cropped)

Bear Island from the South, 1855 (inv. 134)

Near Southeast View of Bear Island, 1855 (inv. 135)

Bear Island from Western Side of N. East Harbour, 1855 (inv. 136)

Sketch from Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1863 (inv. 145)

Boston Harbor, 1850s (inv. 158)

Looking up Portland Harbor, 1863 (inv. 159)

Mount Desert Sketch, 1850s (inv. 185)

(1) While Lane kept a hand in lithography after returning to Gloucester in 1848, and drawings made by him appear to have been used for making prints in at least two instances, his focus was the production and marketing of his oil paintings.

(2) Lane also made preliminary drawings on his canvases. Many of these underdrawings have been captured using infrared reflectography and these images provide another avenue of investigation into Lane’s drawing techniques and working methods.

(3) Novak points out that the paintings represent isolated sections of the drawings and with their lack of vertical edges seem “plucked from a more extensive panoramic view.” Novak, B., American Landscape Painting of the Nineteenth-Century: Realism Idealism and the American Experience (New York, Washington, London: Praeger Publishers, 1969), 112.

(4) Because the drawings have passed through many (well-intentioned) hands, it becomes difficult to surmise what Lane did with them. For example, the vast majority of drawings were annotated by Stevens, so he may have been the person to more permanently join the sheets. Much later, additional annotations were made by archivists and librarians who catalogued the drawings, and in the 1980s, the drawings underwent conservation treatment at a private conservation studio in Arlington, Massachusetts. (Exact treatment steps are not known at this time, but likely included wet cleaning.)

(5) See Drawing Manuals for list of American and British drawing manuals consulted for this research.

(6) Marjorie Shelley, “The Craft of American Drawing: Early Eighteenth to the Late Nineteenth Century", in American Drawings and Watercolors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Volume I, A Catalogue of Works by Artists before 1835, ed. Kevin J Avery (New Haven and London, 2002), 56-60.

(7) Peter C. Marzio, “Drawing by Formula,” in The Art Crusade: An Analysis of American Drawing Manuals, 1820 – 1860. (City of Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976), 31 – 44. (Marzio’s publication includes an appendix of American drawing books published between 1820 and 1860.)

(8) Graphite was easily effaced with India rubber, a substance first developed for this purpose in 1770 by English engineer Edward Nairne. The pencil eraser became common with vulcanization, a curing process developed by Charles Goodyear in 1839 that rendered the rubber more durable. By 1858, the eraser was added to the pencil, an invention patented by Hymen Lipman.

(9) Fessenden Nott Otis, Easy Lessons in Landscape with Instructions for the Lead Pencil and Crayon. (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1853), 5.

(10) Lithographic crayons are also manufactured in varying degrees of hardness, a property that correlates with grease content: harder crayons contain less grease and produce a lighter mark in the final print; softer crayons have more grease and produce blacker marks (in the final print). Like the modern graphite pencil, early lithographic crayons could be sharpened to points, and had endless capacity for tonal range and subtle transitions.

(11) General descriptions of the papers’ weights and surface textures requires some estimating, as the majority of drawings were examined framed and under glass and with mats covering the edges.

(12) Many works were examined over-matted, framed, and behind glass, so close examination of the paper was not possible. However, even when it was possible to examine the paper directly, assessment of method of manufacture was hindered by the absence of original edges and inability to examine the watermarks closely for subtle visual clues that allow the distinction between a handmade paper watermark, (a mark created by virtue of a thinner fiber deposition on a wire sewn into the mold), versus a machine-made paper watermark (a mark impressed in a uniform, still-wet sheet with a dandy roll).

(13) Teresa Fairbanks Harris and Scott Wilcox, Papermaking and the Art of Watercolor in Eighteenth-Century Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 108-110.